Dental Caries: The disease and Its Clinical Management

Part II Clinical caries epidemiology

P123

8 The epidemiology of dental caries

8章 齲蝕の疫学

B. A. Burt, V. Baelum and O. Fejerskov

P123-45

Introduction

導入

Measuring dental caries

齲蝕を評価する

Distribution of caries

齲蝕の分布

Summary

まとめ

References

P124

Introduction

導入

Epidemiology is the study of health and disease in populations, and of how these states are influenced by heredity, biology, physical environment, social environment and human behavior.

疫学は、集団における健康と疾病を、また、これらの状況は

遺伝的生物的物理的環境、社会的環境、人間の行動から、どのような影響を受けているのかを研究する分野である。

It differs from clinical studies in that epidemiology’s focus is on groups of people, often whole populations, rather than on individuals or patients.

疫学と臨床研究の違いは、疫学は個人や何人かの患者ではなく、人々の集団、しばしば母集団に焦点を絞るということにある。

The goal of epidemiological study is to identify the risk of disease that follows certain exposures, so that appropriate preventive interventions may be carried out at the public health and individual levels.

疫学研究の目標は、適切な予防介入が公衆衛生と個人水準で実行できるように、特定の暴露に続いて生じる疾病のリスクを特定することにある。

To achieve this goal, epidemiological study uses a number of different research designs.

この目標を達成するために、疫学研究は、さまざまな研究デザインを利用する。

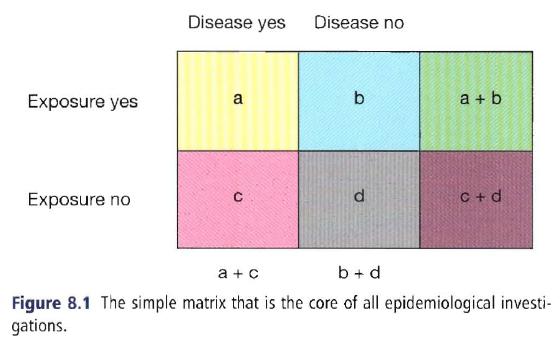

All of them, however, include people with and without the disease in question, and with and without exposure to the correlates of interest.

しかし、あらゆる研究デザインは、対象となっている疾病のある人々とない人々、また関心を引く相互に関連のあるものへの暴露のある人々とない人々からなる。

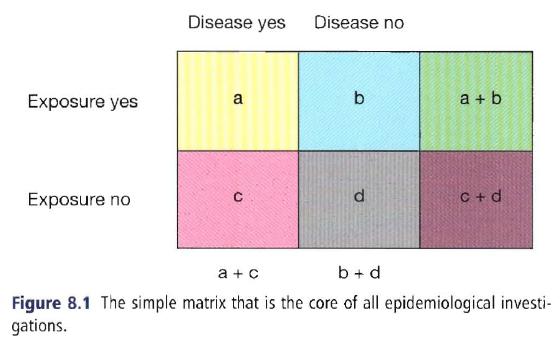

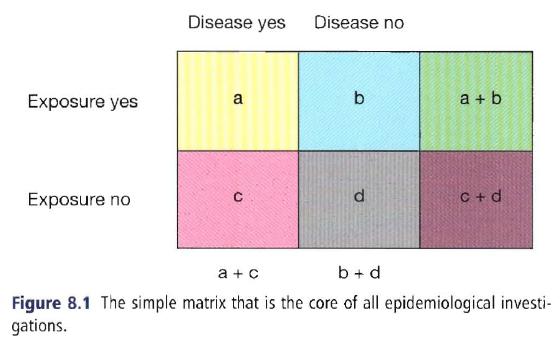

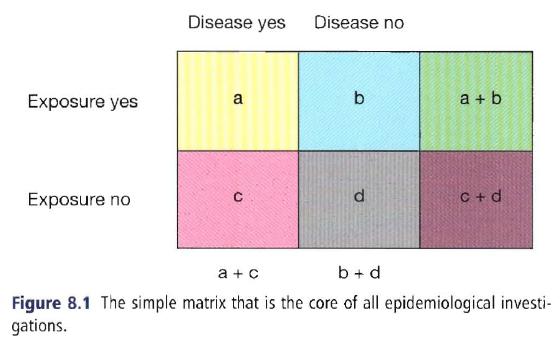

While research designs can become quite involved, Figure 8.1 shows the simple matrix that is the core of all epidemiological investigations.

While research designs can become quite involved, Figure 8.1 shows the simple matrix that is the core of all epidemiological investigations.

研究デザインはかなり複雑となりうるが、Figure 8.1に、あらゆる疫学研究の中核をなす簡単なマトリックスを示す。[2010.1.29]

Many factors are considered to be part of the causal chain in dental caries: bacteria, diet, plaque deposits, saliva quantity and quality, enamel quality, genetic history and tooth morphology have all been studied as possible risk factors for caries (Chapter 29).

多くのファクターが、齲蝕における因果連鎖の一部であると考えられている。齲蝕のリスクファクターの可能性を秘める細菌、食糧、プラークの堆積、唾液の質と量、エナメル質の質、遺伝的経歴と歯の形態のすべてが、研究されている (Chapter 29)。

A risk factor is defined as:

リスクファクターは、以下のように定義される。

An environmental, behavioral, or biologic factor confirmed by temporal sequence, usually in longitudinal studies, which if present directly increases the probability of a disease occurring , and if absent or removed reduces the probability.

その存在が疾病発生の可能性を直接に増加させ、そしてそれが欠如または取り除かれると可能性が減少することを、通常は縦断研究により、時間的順序に確認された、環境的行動的生物的ファクター。

Risk factors are part of the causal chain, or expose the host to the causal chain.

リスクファクターは因果連鎖の一部であるか、宿主を因果連鎖にさらす。

Once disease occurs, removal of the risk factor may not result in a cure (Beck, 1998).

いったん疾病が生じれば、リスクファクターを取り除いても、治癒にはいたらないこともある (Beck, 1998)。

Epidemiology’s role is to identify the risk factors for disease.

疫学の役割は、[集団における]疾病のリスクファクターの特定にある。

As stated in the definition above determining whetherexposure to a potential risk factor leads to a particular disease requires longitudinal study.

上記の定義に述べられている通り、リスクファクターと見込まれるものへの暴露が特定の疾病につながるかどうか、を判断するには、縦断研究が必要である。

Where there is evidence to suggest that a particular exposure is a risk factor, but the relationship cannot be confirmed through prospective study, the exposure is referred to as a risk indicator.

ある暴露がリスクファクターであると示唆する検証があり、しかしその関係が前向き研究により確認出来ない場合は、その暴露はリスクインディケーターと呼ばれる。

Major intraoral entities that are part of the causal chain (e.g. oral microflora, specific dental plaques, and saliva quality and quantity) are dealt with in detail elsewhere in this book and so will not be part of this chapter.

(口内微生物叢、特定のデンタルプラーク、唾液の質と量といった)因果連鎖の一部である主要な口内に存在する物については、他の章に詳しいため、本章では扱わない。

Instead, the distribution of dental caries in populations, and the factors that influence that distribution, are examined here.

代わりに、集団における齲蝕の分布とその分布に影響を与えるファクターを精査する。

A major theme is that severe caries today is increasing ly being recognized as a disease that closely follows a social gradient, so this chapter is broadened to emphasize the important role of the social environment in caries distribution.

重度の齲蝕は、今日ますます、社会的勾配に忠実に従う疾病であると認識されてきており、そこで本章は、齲蝕の分布における社会的環境の役割の重要性をひもとく。[2010.1.30]

After a brief look at some of the issues in caries measurement, the relationships between caries experience and national income levels (as a broad measure of social resources) are examined.

齲蝕の評価におけるいくつかの課題を確認した後、齲蝕経験と(社会資源の指標として)国家の収入水準の関係を調べる。

Then, following a brief consideration of how caries distribution is related to those individual attributes that cannot be changed, e.g. age, race, gender and genetic predisposition, the relationship between caries and socioeconomic status (an individual measure) and social determinants (a community measure) is explored.

そして、齲蝕の分布が、年齢、人種、性別、疾病についての遺伝的素質といった変えることのできない個人的特性に、どれほど関連しているのかを考察し、齲蝕と(個人の指標である)社会経済的地位、そして(地域の指標である)社会的決定要因の関係を検討する。[SESは個人の行動の要約指標、social determinantsは地域のヘルスアウトカムに影響を与えるファクター]

These community-based factors, sometimes called neighborhood characteristics, are now recognized as having a strong influence on caries extent and severity.

近隣特性とよばれるこれらの地域単位のファクターは、近年、齲蝕の広がりと重症度に大きな影響をもたらしている、と認識されている。[multi level analysisのことか?]

Caries is an ancient disease

古代からの病、齲蝕

Dental caries has been making people miserable since at least the time when humans began to develop agriculture.

齲蝕は、少なくとも、人類が農耕を始めるころには、人々を蝕んでいた。

From palentological remains from the Iron Age, it appears that carious lesions in young people sometimes began in occlusal fissures, but developed no further because attrition progressed faster than caries.

鉄器時代の旧人類の遺骨からは、しばしば咬合面裂溝にはじまる齲蝕病巣が認められているが、齲蝕より磨耗の進行する速度の方が上回っていたため、齲蝕がそれ以上進行している様子は認められていない。

This pattern of development can still be seen today, e.g. in some African populations, where the rate of progression on approximal surfaces may also be so low that these lesions are ground away.

アフリカの一部では、今日でもこの傾向が見られるが、隣接面の進行速度も遅いため、齲蝕病巣は磨滅してしまう。

Most lesions found in human remains from the Iron Age were cervical or root caries; coronal caries was relatively uncommon at this time, although it became more common during the time of the Roman Empire.

鉄器時代の人骨の齲蝕病巣の大部分は、歯頚部ないし根面に認められる。歯冠齲蝕は、この時代では比較的蔓延していなかったのだろう。しかし、古代ローマ帝国時代には、歯冠齲蝕は猛威を振るうことになった。

Roman remains give evidence that some teeth with large coronal cavities had obviously been treated.

ローマ人の遺骨には、明らかに治療をしたと思われる、大きな歯冠齲蝕の痕跡がみられる。

The moderate caries experience found in Britain during the Anglo-Saxon period (sixth to seventh centuries) had changed little by the end of the Middle Ages (Moore & Corbett, 1971, 1973).

イギリスでは、アングロサクソン時代(16-17世紀)から中世の終焉まで、齲蝕の蔓延の程度は、中等度のままで、ほとんど変化がなかった (Moore & Corbett, 1971, 1973)。

Increased consumption of processed food and greater availability of sugar were probably chiefly responsible for the development of the modern pattern of caries.

現代の齲蝕の傾向は、主に、加工食品の消費の増大と砂糖の普及に原因がある。[2010.2.2]

Import duties on sugar in Britain were relaxed in 1845 and completely removed by 1875, a period during which the severity of caries increased greatly (Corbett & Moore, 1976; Lennon et al., 1974).

イギリスの砂糖の輸入税は1845年から緩和され、1875年には完全に撤廃された。齲蝕の時代の始まりである (Corbett & Moore, 1976; Lennon et al., 1974)。

By the end of the nineteenth century, dental caries was well established as an epidemic disease of massive proportions in most of the economically developed countries (Burt, 1978).

19世紀末までに、経済発展を遂げた国々の多くで、齲蝕は地域的疾病の地位を確立していた (Burt, 1978)。

The severity of the caries epidemic in the late nineteenth century led directly to the establishment of public dental services, which first appeared in the Scandinavian countries.

19世紀末には、齲蝕の地域的流行の厳しさは、公的歯科医療の設立へとつながった。スカンジナビア諸国でのことである。

P125

Measuring dental caries

齲蝕の評価

To study caries and its distribution in populations, it must be possible to measure it validly and reliably, and then put those measurements together in some systematic fashion so that caries distribution in one group can be compared with that in another.

齲蝕と集団におけるその分布を研究するためには、ある集団における齲蝕の分布と他の集団における齲蝕の分布を比較できるように、妥当性と信頼性のある齲蝕の評価とその評価の体系化が必要である。

Since the disease of dental caries occurs on a continuum, from the earliest demineralization to cavitation, it is clearly important to have clear rules, or criteria, for the conditions under which caries is judged to be present.

齲蝕は、脱灰初期から齲窩にいたるまで連続的に生じるため、それが齲蝕なのかどうか、はっきりとした規定や基準を設けることは、重要である。

(Chapter 9 shows the impact of using differing measurement criteria on prevalence and severity data).

(評価基準のばらつきが、有病割合と重症度の資料にもたらす影響については、9章に詳しい)

Valid and reliable measurement is the basis of any science, including epidemiology, where an index (a numerical scale with upper and lower limits, with scores on the scale that correspond to specific criteria) is usually required to obtain a precise expression of disease distribution in a group.

妥当性と信頼性の評価は、ありとあらゆる科学の基本であり、とりわけ疫学では、指数(特定の基準に一致する尺度に基づくスコアで上限と下限のある数値指標)は、通常集団における疾病の分布を明瞭に説明することを要求される。

The properties of an ideal index are listed in Box 8.1.

理想的な指数の性質をBox 8.1に掲げる。

Index scores usually give no picture of clinical conditions (e.g. what does a plaque index score of 1.2 look like?), and in the past were often statistically mistreated when averages were computed from ordinal scales, but they have value when compared with the index scores from other groups measured in a similar way.

指数スコアは、通常臨床的状況を表さず(たとえば、プラーク指数1.2とは?)、また過去には順序尺度から平均を算出するなど、しばしば統計的に誤って処理されていた。しかし、指数スコアは、似た方法で評価されたほかの集団の指数スコアと比較する場合には、価値がある。[2010.2.3]

While various indexes for measuring caries were suggested during the 1920s to the early 1930s, it was only with Dean’s studies of naturally occurring fluoridated water in the 1930s that a practical method was developed and used.

1920年代から1930年代初頭にかけて、齲蝕を評価するためのさまざまな指数が提案され、実用的方法が開発、利用された1930年代には、Deanによる天然水中のフッ化物の研究が行われた。

Dean and his colleagues (Dean et al., 1942) counted the numbers of teeth in the mouth with obvious caries (i.e. cavities).

Deanとその同僚は、あきらかな齲蝕(すなわち齲窩)の歯の本数を数えた (Dean et al., 1942)。

Filled teeth and teeth missing due to caries were added in, so that the index score included all teeth that had been attacked by caries.

齲蝕の影響を受けたすべての歯を指数スコアに反映させるため、齲蝕のために充填した歯と喪失歯も加算した。

The first description of what is now known as the DMF index came from extensive studies of dental caries among children in Hagerstown, Maryland, USA, in the 1930s (Klein et al., 1938).

現在、DMF指数として知られているものが最初に記述されたのは、1930年代、USAのMaryland州Hagerstownの小児の齲蝕の大規模な調査である (Klein et al., 1938)。

After that, the DMF index became the most used of all dental indexes.

その後、DMF指数は、齲蝕の指数の中では、最もよく利用される指数としての地位を確立した。[2010.2.4]

The DMF index

DMF指数

As originally described, D was for decayed teeth, M for teeth missing due to caries and F for teeth that had been previously filled.

もともとは、Dは齲歯、Mは齲蝕による喪失歯、Fは充填歯のことであった。

Filled teeth were assumed to have been unequivocally decayed before restoration.

充填歯は、修復される前には間違いなく齲蝕であった、と仮定していたのである。

The index could be applied to teeth as a whole (designated as DMFT), or applied to all surfaces of the teeth (DMFS).

この指数は、すべての歯 (DMFT)、ないし歯面 (DMFS) に適応される。

The DMFT score for anyone individual can range from 0 to 32, in whole numbers, while the mean DMFT score for a group can have decimal values.

個人のDMFTスコアは0-32の整数となるが、集団のDMFTスコアの平均値は小数値となる。

The index can be modified to deal with such factors as filled teeth that have redecayed, crowns, bridge pontics and any other particular attribute required for study.

この指数は、改変され、二次齲蝕、クラウン、ポンティック、研究に必要なその他の属性といった要素を充填歯として扱う。

It can also be applied with varying criteria for what constitutes caries.

DMF指数は、齲蝕を構成する、さまざまな基準にも適応される。

The original intention to scored only when there was cavitation has largely given way to scoring systems which record caries at all stages from the earliest enamel caries through to cavitation.

齲窩のある時のみカウントするという、もともとの意図は、初期エナメル質齲蝕から齲窩までのすべての段階を齲蝕として記録する、スコアリング体系に取って代わられてきている。

An example of the latter is the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS), which records caries on a six-point ordinal scale (Pitts, 2004).

後者の例には、国際齲蝕検出評価体系 (ICDAS) があり、これは齲蝕を6点の順序尺度で記録する (Pitts, 2004)。

An otherexample is a scale that disting uishes between caries progress in active and inactive lesions (Nyvad et al., 1999).

その他には、進行性と非進行性の齲蝕を区別する基準がある (Nyvad et al., 1999)。

As a result, DMF scores where caries is measured over its full range of development are higher than those where only cavitation, i.e. a later stage of caries progression, is used as the criterion for decayed teeth.

結果として、DMFスコアは、齲窩のみをカウントする場合よりも、あらゆる進行をカウントする場合の方が大きくなる。

The DMF index has been used widely since its introduction in 1938 because it meets a number of the criteria for an ideal index (Box 8.1).

DMF指数は、1938年に導入されて以来、幅広く利用されている。というのは、この指数は理想的指数の基準を数多く満たしているからである (Box 8.1)。

For example, it is simple, versatile, statistically manageable and reliable when examiners have been trained.

例えば、DMF指数は、簡単で、融通が利き、統計的に扱いやすく、検査員が訓練を受けていれば、信頼性がある。

However, the DMF does have its limitations, and the main ones are listed in Box 8.2.

しかし、DMFには欠点もある。主なものをBox 8.2に示した。

The limitations of the DMF index today frequently relate to moden preventive and restorative technology.

DMF指数の欠点は、今日の予防、修復技術としばしば関連している。

For example, there were no sealants or adhesive resins when the DMF index was first developed.

例えば、DMF指数が開発された頃には、シーラントも接着樹脂も開発されていなかった。

There are two reasonable approaches for adapting the DMF to deal with sealants.

DMFをシーラントに適応させるための、2つの妥当な手法がある。

One says that the sealed tooth is not restored in the usual sense and should therefore be considered sound.

1つは、シーラント歯は通常、充填ではなく、健全であるをみなすべきである、というものである。

The other says that it has required hands-on, one-to-one dental attention, and so should be considered a filled tooth.

もう1つは、シーラントには歯科診療が必要であり、充填歯とみなすべきである、というものである。

Probably the best way to deal with sealed teeth is to put them in a category by themselves, S for sealed.

たいていシーラント歯を扱う最良の方法は、シーラントを示す、Sという分類を作ってしまうことである。

The DMFS index would then become DMFSS.

DMFS指数は、DMFSSになる。

Depending on the study’s purpose, thes teeth can be left separate, included with for regarded as sound.

S歯は、Fに含まれるか、健全歯とみなされるが、研究の目的によっては分けられたままとなる。

The DMF index today is really out dated as a measure of caries incidence and severity, and may actually be more valid as a measure of treatment received.

DMF指数は、今日、齲蝕の発生数と重症度の指標としては、実際のところ時代遅れであり、また、受療の評価としては、わりと妥当である。[2010.2.5]

It is philosophically questionable to use an index for a disease that is so dependent upon the treatment judgments of many practitioners, and the combination of previous treatment (i.e. the M and F components) with current treatment need (the D component) is not used elsewhere in public health surveillance.

多くの臨床家の治療判断に大きく依存する疾病の指数を利用することは、哲学的に疑問であり、以前の治療 (M, F) と現在の治療ニーズ (D) の組み合わせは、他の公衆衛生調査では利用されていない。

An objective measure of caries activity (e.g. a marker of active disease) would be preferable to clinical judgment for many purposes, but because valid markers for caries are elusive, scoring caries activity is still based on clinical acumen (Nyvad et al., 1999).

齲蝕活動性の客観的評価(たとえば、活動性疾病マーカー)は、さまざまな目的の臨床判断で好まれるが、齲蝕の妥当なマーカーはエルーシブなため、現状、齲蝕活動性のスコアリングは臨床的洞察に基づいている (Nyvad et al., 1999)。

On the credit side DMF has been used for generations and still has some use in monitoring trends over time.

DMFは長年にわたり利用されてきており、いまだに経年的な傾向の把握に利用されている。

Its mix of treated and untreated caries measures also gives it some value in health services research.

未治療齲蝕と治療済み齲蝕の評価を、組み合わせることは、医療の研究においても、価値がある。

Until a more objective measure is developed and accepted then some modification of DMF will continue to be the principal index used to express the caries status of a population.

より客観的な評価が開発され、普及するまでは、改変DMFが、集団の齲蝕状況を表現する指数の第一選択であり続けそうだ。[2010.2.6]

P126

Other measures of caries

齲蝕のその他の評価

Other methods of measuring dental caries, using different philosophical bases, have been suggested from time to time.

ときどき、DMFとは異なる哲学に基づいた齲蝕を評価する方法が提案される。

One is Grainger’s hierarchy, an ordinal scale designed to simplify the recording of the caries status of a population, which uses five zones of severity of the carious attack (Grainger, 1967).

その1つがGraingerのヒエラルキーであり、これは集団における齲蝕の状況の記録を単純にする順序尺度であり、齲蝕の重症度を5つのゾーンで考える (Grainger, 1967)。

This method was based on a landmark paper of Klein and Palmer (1941), which presented a caries susceptibility order for the teeth, an ordering which has changed little down the years (Macek et al., 2003).

Graingerのヒエラルキーは、KleinとPalmer (1941) の有名な論文に基づいており、歯の齲蝕感受性の序列を示し、その序列は昔からほとんど変わっていない (Macek et al., 2003)。

Several studies confirmed the validity of the hierarchy (Katz & Meskin, 1976; King man, 1979; Poulsen & Horowitz, 1974).

多くの研究が、このヒエラルキーの妥当性を確認している (Katz & Meskin, 1976; King man, 1979; Poulsen & Horowitz, 1974)。

The Grainger hierarchy could be useful in public health surveillance, but it has received little further use.

Graingerのヒエラルキーは、公衆衛生調査では便利であるが、ほとんど使われていない。

‘Composite’ indicators have been suggested that attempt to measure health rather than disease by statistically weighting healthy restored teeth differently from missing or decayed teeth (Sheiham et al., 1987).

‘合成’指標は、喪失歯や齲歯と健康な修復歯の重み付けを統計的にかえることで、疾病ではなく健康を評価しようとしている (Sheiham et al., 1987)。

The first of these is the FS-T, which sums the sound and well-restored teeth.

第1はFS-Tとよばれ、健全歯と修復歯の合計である。[2010.2.8]

The second is T-Health, which seeks to measure the amount of healthy dental tissue and ascribes descending numerical weights for a sound healthy tooth, a well-restored tooth and a decayed tooth.

第2に、健全な歯の組織の量を評価し、また健全歯、修復歯、齲歯の順に数的重みをつける。

These are conceptually sound approaches to measuring dental health and function (rather than disease), and they probably deserve more attention than they have received.

これらは、歯の(疾病ではなく)健康と機能を評価する概念的に健全な手法であり、たぶん現状より評価されるにふさわしいものである。[ん?sheihamに、なにかつかまされたか?]

An offshoot of the present-day skewed distribution of caries is the significant caries index (SiC) (Bratthall, 2000; WHO, 2005).

今日の齲蝕の傾斜分布から派生したのが、SiC指数である (Bratthall, 2000; WHO, 2005)。[正規分布しない状況の要約には、パーセンタイルも推奨されています]

The SiC is not a new index, but rather is a form of data presentation to help give a better picture of caries distribution in the population.

SiCは新しい指数ではなく、集団における齲蝕分布の状況をよりよく示す資料である。

It is the mean DMF score for the third of the population that is most affected by caries, intended to be used along side the mean DMF of the whole population to give a more complete summary of its caries distribution.

SiCは集団の中の齲蝕の多い1/3のDMFスコアの平均値であり、より完全な要約として集団全体のDMFの平均値に添えて利用される。

The more skewed the distribution, the greater the gap between the mean DMF and the SiC.

分布が歪んでいるほど、DMFの平均値とSiCの差は大きくなる。

Criteria for diagnosing coronal caries

歯冠齲蝕の診断基準

There is no global consensus on the criteria for diagnosing dental caries, despite a vast quantity of words on the subject.

齲蝕の診断基準については、大量の言葉が語られているが、その実、国際的基準はない。

Apart from the inherent problem of diagnosing a borderline lesion, the major philosophical issue comes with scoring the early carious lesion which has not yet become cavitated.

境界線直上の病巣の診断につきものの課題は別にしても、まだ齲窩を形成していない初期齲蝕病巣のスコアリングにともなう哲学的課題がある。

These lesions appear as discolored fissures without loss of substance, as a ‘white spot’ on visible smooth surfaces, or radiographically as an early interproximal shadow.

実質欠損のない変色した裂溝、平滑面の‘白斑’、隣接面のレントゲン上の陰影などである。

The issue is that not all non-cavitated lesions progress to dentinal lesions requiring restorative treatment, and active non-cavitated lesions should receive non-operative treatment to prevent any further caries progression.

この課題の核心は、すべての齲窩のない病巣が修復治療の必要な象牙質病巣に進行するわけではなく、また活動性非齲窩性病巣は、齲蝕の進行を妨げるために非外科的治療を受けるべきである、ということにある。

With non-operative treatment (or sometimes even without it), a good proportion of them will remain static or even remineralize (Pitts, 1993).

活動性非齲窩性病巣は、非外科的治療を受ければ(あるいは、なにもしなくても)、そこそこ停止するか、あるいは再石灰化する (Pitts, 1993)。

These lesions arethus reversible, as opposed to dentinall esions, which are usually considered irreversible.

象牙質齲蝕は通常、非可逆性であると考えられているが、これらの病巣は可逆性であるのだ。

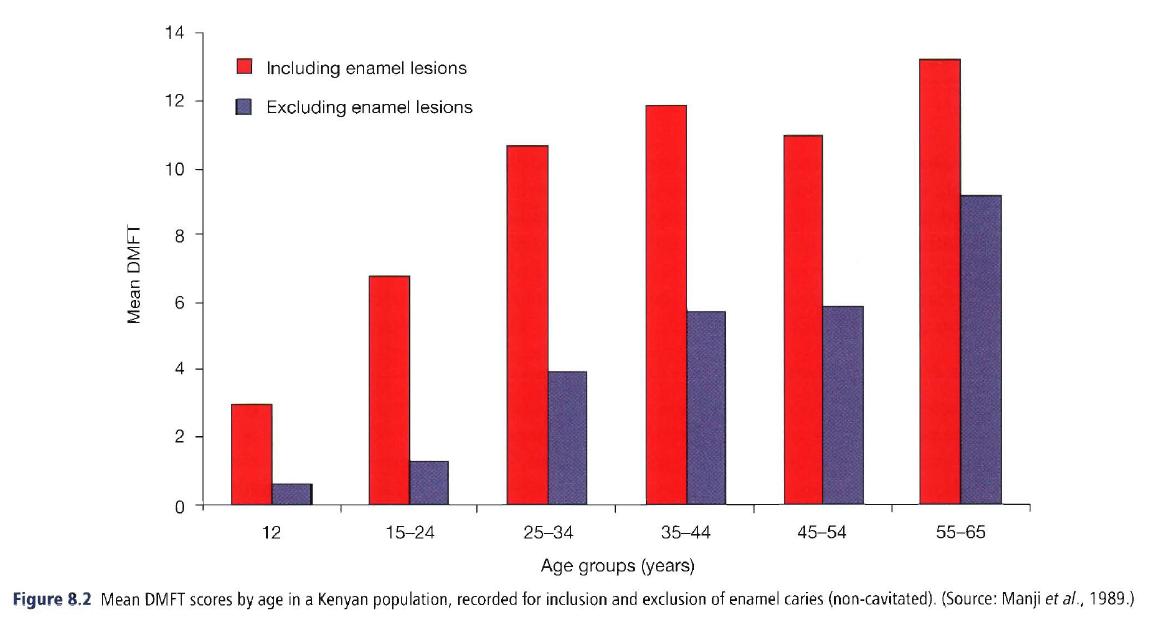

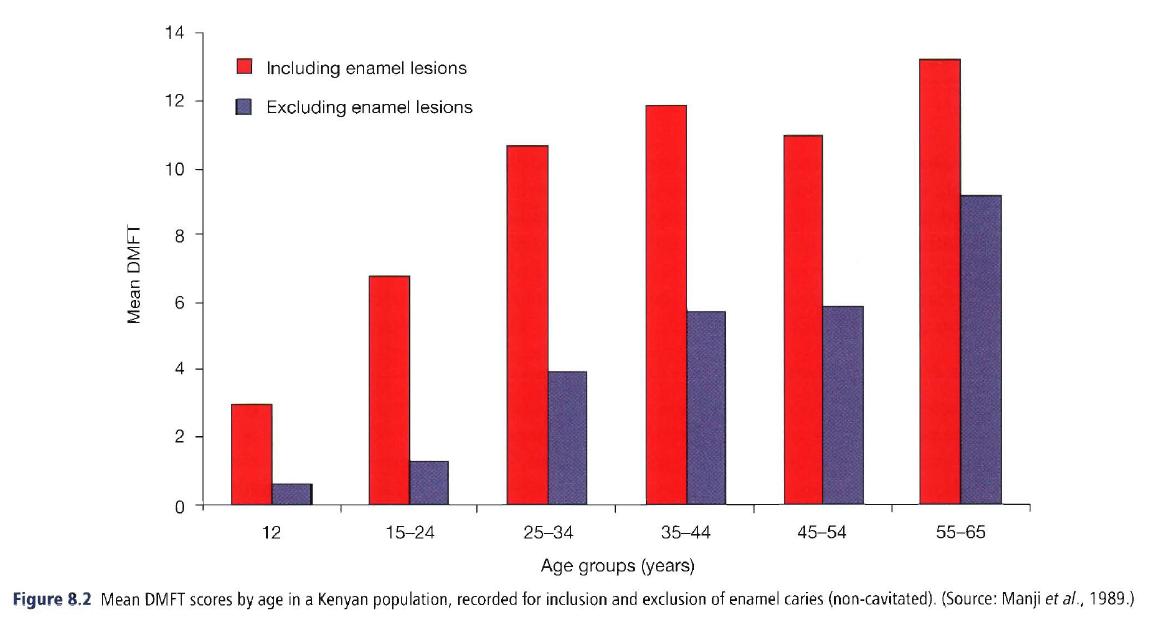

Because there are usually more non-cavitated than cavitated lesions at anyone time in both high-caries and low-caries populations (Pitts & Fyffe, 1988; Bjarnason et al., 1992; Ismail et al., 1992; Machiulskiene et al., 1998), the decision of whether to include or exclude them, and how to express them if included, can make a substantial difference in the oral health profiles obtained (Chapter 9).

普通は、いつ、いかなる場所であれ、齲窩のある病巣より、齲窩のない病巣の方が多い (Pitts & Fyffe, 1988; Bjarnason et al., 1992; Ismail et al., 1992; Machiulskiene et al., 1998) ため、齲窩のない病巣を含むか除くかの決断と、もし包含するならそれをどう表すのかは、口内保健の輪郭に相当なずれをもたらす。

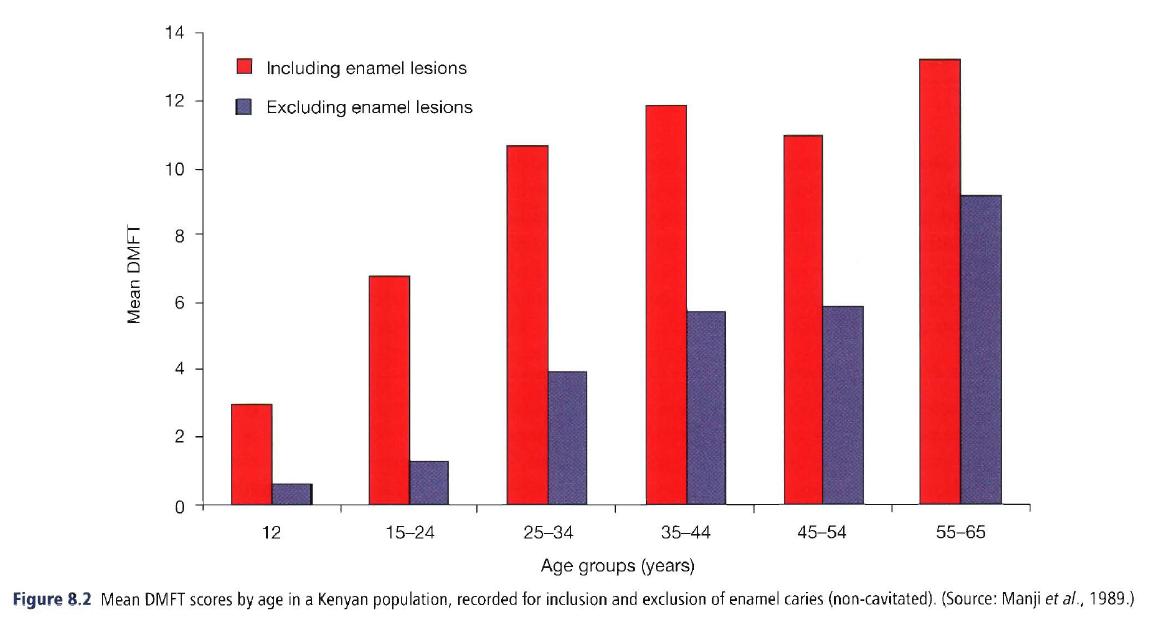

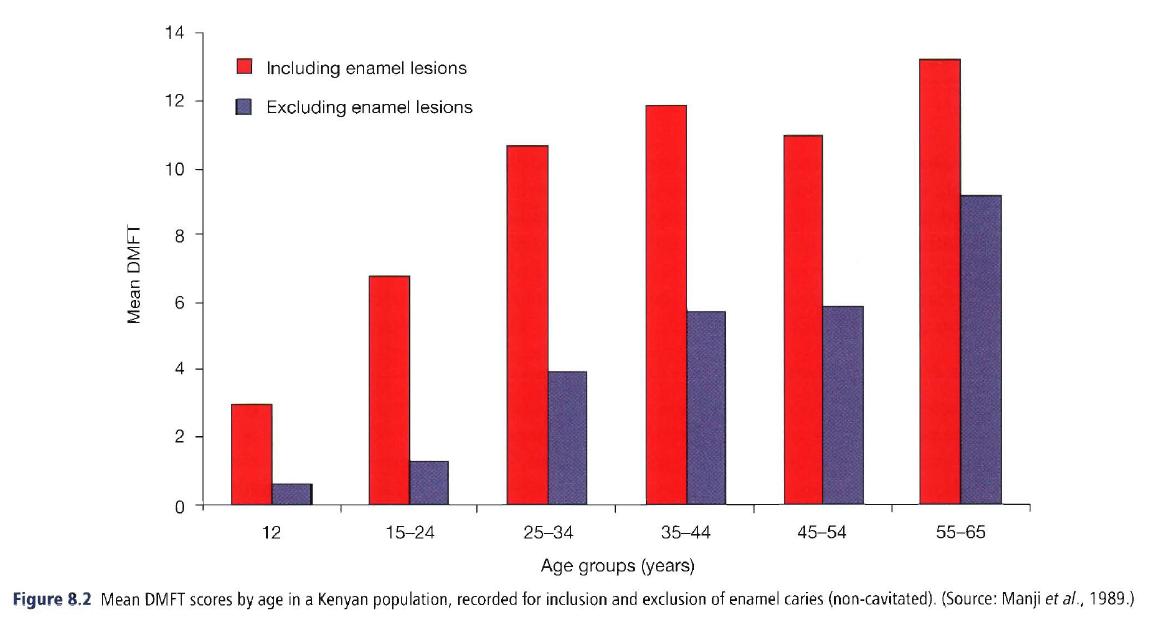

This is illustrated in Fig. 8.2, where in surveys in Kenya the carious lesions were recorded as both cavitated and enamel-only (i.e. non-cavitated).

This is illustrated in Fig. 8.2, where in surveys in Kenya the carious lesions were recorded as both cavitated and enamel-only (i.e. non-cavitated).

齲窩のある齲蝕とエナメル質齲蝕(齲窩のない齲蝕)の両方を記録しているKenyaでの齲蝕の調査をFig. 8.2に示す。[2010.2.11]

There is a marked difference in any caries profile depending on whether non-cavitated lesions are included or not.

齲窩のない齲蝕の含除により、齲蝕の輪郭には相当な違いがある。

P127

Examples of these two broad approaches to diagnostic criteria for dental caries are shown in Box 8.3.

齲蝕の診断基準に対する2つのアプローチの例をBox 8.3に示す。

European investigators have long recorded caries on a scale that extends through the full range of disease from the earliest detectable non-cavitated lesion through to pulpal involvement (Backer Dirks et al., 1961).

欧州の調査員は、最初期検出可能非齲窩性病巣から、歯髄侵襲性齲蝕病巣まで、あらゆる進行段階を評価できる尺度で齲蝕を記録している。

The criteria in Box 8.3 were first published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1979 (WHO, 1979), and will be referred to as the D1-D3 scale.

Box 8.3の基準は、1979年にWHOから公表されたもので、D1-D3尺度と呼ばれている。

(There is a D4 for pulpal involvement, but that recording is seldom contentious.)

(D4もあるにはあるが、めったに使われない)

More recently, clinical researchers in Europe have expanded on this concept to produce a scale with up to 10 points, combining increasing depths of lesion development with clinical signs of activity or inactivity (Machiulskiene et al., 1999; Nyvad et al., 1999; Pitts, 2004).

より近年、欧州の臨床研究者は、病巣進行の深さと活動性あるいは非活動性の臨床上のサインを組み合わせて、この尺度を10ポイント制に改変している (Machiulskiene et al., 1999; Nyvad et al., 1999; Pitts, 2004)。[2010.2.12]

However, investigators in North America, Britain and other English-speaking countries have until recently used visual tactile means to record caries as a dichotomous condition, meaning that caries was recorded only as present or absent.

一方、North America、Britain、そのほかの英語圏の検査者は、齲蝕の有無のみを、ななんと、視診と触診に頼って記録している。

(This is referred to here as the dichotomous scale.)

(ここでは、これを、2点尺度[有無のみの評価]と呼ぼう。)

In the dichotomous recording , caries was only noted when it reached the level of dentinal involvement (Horowitz, 1972), i.e. the D3 level.

2点尺度では、齲蝕は象牙質侵襲性(D3)に達したもののみをカウントする (Horowitz, 1972)。

The D1-D3 scale requires the teeth to be dried and receive a longer, more meticulous examination, although with well-trained examiners this can be done even under fairly primitive field conditions.

D1-D3尺度は、歯の乾燥と、長く細やかな診査を必要とするが、よく訓練された検査者であれば、かなり原始的な現場の条件下であっても、判定は可能である。

A scoring system based on the D1-D3 scale is a necessity in cariology research studies, for it permits identification of lesion initiation, progression and regression.

D1-D3尺度に基づいたスコアリング体系は、病巣の初期、進行、逆行を同定できるので、齲蝕研究には不可欠である。

Research questions on the conditions under which early lesions progress, regress or remain static can only be answered with a measurement scale of this nature.

どのような状況下で、初期病巣が進行するのか、逆行するのか、停止するのかという疑問は、この性質をもつ尺度によってのみ、答えられる。

Its use demands meticulous examiner training, since because D1 lesions are capable of remineralizing back to sound enamel it becomes difficult to differentiate examiner error from natural phenomena.

D1病巣は再石灰化して健全なエナメル質になりうるため、検査者による診断の過誤と自然現象を区別するのが困難であることから、D1-D3尺度は、細やかな検査者のトレーニングを要求する。

This may influence the assessment of absolute changes, although in the absence of bias it should not affect the contrast between groups.

これは絶対的な変化の評価に影響するが、バイアスがなければ、集団間の比較[相対的な変化の評価]には影響がない。

There is less consensus on whether the D1-D3 scale should be used in large-scale surveillance surveys, for arguments can be made both ways.

D1-D3尺度と2点尺度[有無のみの評価]、両方について議論があり、D1-D3尺度が大規模な実態調査に使われるべきかどうかについての合意はない。

Surveillance surveys are conducted at multiyear intervals to address the broad questions of whether disease levels are increasing or decreasing so that appropriate public policy can be formulated.

適切な政策を形作るため、疾病水準の上下を把握するため、実態調査は複数年間隔をあけて実施される。

For comparisons over time, it is clear that disease-measurement criteria need to be similar, and generally the simpler the system the better the examiner reliability.

長年の比較のために、疾病の評価基準は類似していている必要があるのは、明らかであり、一般に、体系が単純なほど検査者の信頼性はよくなる。

However, measuring caries only when cavitation can be detected underestimates the true extent of caries.

しかし、齲窩のあるときのみ齲蝕を評価することは、齲蝕の真の広がりを過小評価する。

Some see measuring caries only when cavitation is present as serving to perpetuate the old-fashioned ‘drill-fill-bill’ approach to tooth repair, while others see the opposite, that the same undesirable outcome will come from recording early demineralized lesions that should receive non-operative treatment.

齲窩のあるときのみ齲蝕を評価することは、歯の修復の遺物である‘形成-充填-請求’アプローチの延命であるとする人もいる。また、ある人は、正反対なことに、非外科的治療を受けるべき初期脱灰病巣を記録することは、好ましくない結果が生じる、と懸念する人もいる。

This discussion is likely to continue.

この議論は、続きそうである。

P128

Measuring caries treatment needs

齲蝕治療ニーズの評価

Assessment of the caries treatment needs of a group, at first glance, appears to be nothing more than the segment of a mean DMF score assessed from a survey.

集団の齲蝕治療ニーズの評価は、一見、調査から評価されるDMFスコアの平均値で、こと足りる、ように見える。

This approach, however, has been shown not to work, for the reasons listed in Box 8.4.

しかし、Box 8.4に示すように、このやり方は、うまく機能しないことが、明らかとなっている。[2010.2.13]

Because surveys are usually conducted in field conditions that are less than ideal, relative to the dental office, it would be expected that surveys detect fewer carious lesions than practitioners do.

調査は通常、歯科診療所と比較して、理想的とは言いがたい状況で実施されるため、検出される齲蝕の数は、診療所で行われるよりも少なくなると思われる。

However, that begs the question of which assessment is ‘correct’.

しかし、これは、どのような評価が‘正しい’のかという疑問に帰結する。

Field surveys can miss early lesions, but practitioners can also overtreat.

現地調査は、初期病巣を見逃すかもだが、臨床医は過剰治療するかも、なのである。

To add to the uncertainty, treatment plans for the same patients have been shown to vary drastically from one dentist to another (Espelid et al., 1985; Bader et al., 1993; Nuttall et al., 1993).

この不確実性に加えて、同じ患者でも、歯科医師により治療計画は大きく異なることが、示されている (Espelid et al., 1985; Bader et al., 1993; Nuttall et al., 1993)。

The difficulty of determining treatment needs by survey was illustrated after a 1978 national dental survey in Britain.

調査により治療ニーズを決定することの難しさは、1978年のBritainでの歯科全国調査で明らかとなった。

In the course of this survey, 720 dentate adults in Scotland agreed to permit their dental records to be followed over subsequent years.

この全国調査の過程で、Scotlandの720の歯のある成人が、複数年の歯の記録に同意した。

After 3 years, records showed that while 863 teeth in this group had been assessed as needing restorative care in the survey, 3108 actually had been restored.

調査では、本集団の863本の歯が、修復治療の必要があると評価されたが、その3年後には、3108の歯が治療を受けていた。

One might think that this finding could be explained by early lesions missed under the less-than-ideal survey conditions, but if that explanation is accepted then the next finding has no logic at all: of the 863 teeth classified as needing restorative treatment in the survey, only 271 (31%) were in the 3108 restored (Nuttall, 1983).

この発見は、理想的ではない調査状況による、初期病巣の見落としにより説明される、と考える人も、1人はいるだろう。よしんば、それで納得しても、次の発見に説明はつくのだろうか。治療を受けていた3108本のなかで、この調査で治療ニーズがあると評価された863本に含まれるのは、271本(863本の31%)[3108本の9%]なのだ (Nuttall, 1983)。

This shows that the care carried out, rather than being an extension of the survey results, in fact bore no relation to them.

これは、調査結果の延長上に、治療があるのではなく、調査結果と実際の治療には、関係がないことを示している。

This outcome is not easy to explain, but it would seem to illustrate the diverse approaches that dentists take towards diagnosing caries.

この結果を説明することは、やさしいことではないが、齲蝕の診断に対する、歯科医師のアプローチは、さまざまあることを示しているようだ。

It has been shown that dentists bring their own characteristics and biases to the task, and are largely guided by their inclinations towards particular intervention strategies.

このことから分かるのは、歯科医師は、仕事に対して自己の持ち味とバイアスをもっている、ということと、特定の介入戦略に対する性向を主な判断材料とする、ということである。

As a result, it is hardly surprising that there is substantial divergence between dentists in the nature of their diagnostic decisions (Bader & Shugars, 1997).

結果として、その性質を踏まえれば、診断は、歯科医師によって大きな隔たりがあるというのは、驚く事ではない (Bader & Shugars, 1997)。

‘Dental needs’ in the USA were assessed by examiners in the first National Health and Examination Survey (NHANES 1) of 1971-1974, and 65% of the population were judged as being in need of restorative care (US Public Health Service, NCHS, 1979).

USAにおける‘歯科ニーズ’は、1971-1974年のNHANES 1により評価され、全体の65%は、修復治療のニーズがあると判断された (US Public Health Service, NCHS, 1979)。

A similar assessment was made with the first national survey of schoolchildren in 1979/80, when 37% of schoolchildren were judged to be in need of restorative care (US Public Health Service, NIDR, 1982).

同様の評価が、1979/80年の第1回全国学童調査で行われ、学童の37%に修復治療のニーズがあると判断された (US Public Health Service, NIDR, 1982)。

These figures have received little use.

これらの数字は、ほとんど利用されていない。

In later national surveys (US Public Health Service, NIDR, 1987, 1989), treatment needs assessments were not carried out.

その後の全国調査 (US Public Health Service, NIDR, 1987, 1989) では、治療ニーズの評価は、実施されなかった。

The most recent national surveillance survey in the USA, for which data were collected during 1999-2002, reported that 16.1% of children aged 12-15 years had at least one decayed tooth (enamel or dentinal cavitation level), but the issue of ‘treatment needs’ was not brought up (Beltnin-Aguilar et al., 2005).

1999-2002年に採 取されたUSAの全国調査によると、12-15歳児の16.1%は少なくとも1つ以上の齲歯(エナメル質あるいは象牙質の齲窩)を有していたが、‘治療ニーズ’は提示されなかった (Beltnin-Aguilar et al., 2005)。[2010.2.14]

P129

The WHO includes a subjective treatment-need assessment by the examiner as part of its Pathfinder survey method (WHO, 1997), although it is not known how well these estimates approximate treatment actually carried out.

WHOは、パスファインダー調査 (WHO, 1997) の一環として、検査者による主観的な治療ニーズの評価を盛り込んだが、実際に行われた隣接面治療をどの程度見積もっているのかは、不明である。

WHO also has developed a broad-based approach to determining needs in low-income countries through what it calls a situation analysis, an enhancement of Pathfinder survey data with information on population trends, school enrollment figures, per capita income and health-care resources (WHO, 1980).

WHOは、いわゆる状況分析、集団の傾向の情報をもったパスファインダー調査の資料の強化、学校入学者の数字、一人当たりの収入と医療資源を通じて、低所得国家におけるニーズを決定するための広範なアプローチを開発している。

Distribution of caries

齲蝕の分布

Global distribution

世界的な分布

Caries has historically been seen as a disease of the high-income countries, with a low prevalence in poorer countries.

齲蝕は歴史的に、高所得国家の疾病であり、低所得国家における有病割合は低い。[2010.2.15]

The most obvious reason for this pattern is usually considered to be diet: high consumption of refined carbo-hydrates and other processed foods in the high-income countries and hunting and subsistence farming in the low-income countries.*

この傾向の最も著名な理由は、通常、食事にあると考えられている。高所得国家における精製された炭水化物と加工食品の過剰摂取、そして低所得国家における最低限の自給自足である。*

Some of the historic patterns of high attrition, little coronal caries and moderate prevalence of root caries described above, can still be found in some parts of the world, but they are fast disappearing as once-isolated populations increasingly adopt the cariogenic diets and cultural lifestyles of the high-income world.

上記した、強い磨滅とほとんどない歯冠齲蝕、中程度の有病割合の根面齲蝕という歴史的な傾向は、いまだに世界の一部で確認される。しかし、かつては孤立していた集団が、高所得世界の齲蝕原性食品と文化的生活習慣に適応していくにつれて、これらは消えてきている。

* The World Bank classifies countries as high-income, high middle-income, low middle-income and low-income.

* 世界銀行は、国家を、高所得国家、中高所得国家、中低所得国家、低所得国家に分けている。

These terms replace such words as developed/developing and industrialized/non-industrialized.

これらは、先進国、開発途上国あるいは工業国、非工業国といった言葉と置き換えされる。

See the World Bank website:

世界銀行の公式ウェブサイト:

http://www.worldbank.or.gldata/countryclass/classgroups.htm

There is good evidence that this historical pattern was clearly changing by the later years of the twentieth century.

この歴史的な傾向が、20世紀の終焉までに、疑いようもなく変化してきているという、すぐれた検証がある。

First, there was evidence that caries experience in some low-income countries had risen in the years after World War II (1939-1945) (Moller et al., 1978), although this change was by no means universal, with some populations, notably in Africa, remaining relatively unaffected (Chironga & Manji, 1989; Mosha & Robison, 1989; Manji & Fejerskov, 1990; Baelum et al., 1991; Mosha & Scheutz, 1992; Mosha et al., 1994).

第1に、この変化は、決して普遍的なものではなく、Africaなどいくつかの国では、比較的この変化が見られないのであるが (Chironga & Manji, 1989; Mosha & Robison, 1989; Manji& Fejerskov, 1990; Baelum et al., 1991; Mosha & Scheutz, 1992; Mosha et al., 1994)、低所得国家の一部では、第二次世界大戦(1939-1945年)以降、齲蝕経験が上昇してきているということである (Moller et al., 1978)。[Mollerは正しくは、Møller]

The second change is the marked reduction in caries experience among children and young adults in high income-countries, a trend that first became evident in the late 1970s (Burt, 1978).

第2に、1970年代の後半から始まった、高所得国家の小児と若年者の齲蝕経験の、目を見張る減少である (Burt, 1978)。

This change affects the oral conditions of the whole population in due course as today’s younger cohorts progress through the lifespan.

こちらの変化は、今日の若年者の加齢にともない、近いうちに、集団全体の口内状況に影響する。

WHO maintains the Global Oral Health Data Bank, a collection of surveillance data from most of the world’s countries.

WHOはGlobal Oral Health Data Bankを維持しており、世界のほとんどの国から調査資料を収集している。

As in any surveillance system where a data collection protocol is used in a multitude of different situations by different people, there are likely to be some in consistencies in these data.

どのような調査制度にでも見られるが、資料採取手順は、さまざまな人々により異なる状況により、利用されており、これらの資料には、何らかの一貫性のなさがありがちである。

Still, the data bank provides an invaluable profile of broad trends in oral health.

それでも、データバンクは口内保健のさまざまな傾向の計り知れない輪郭をもたらす。

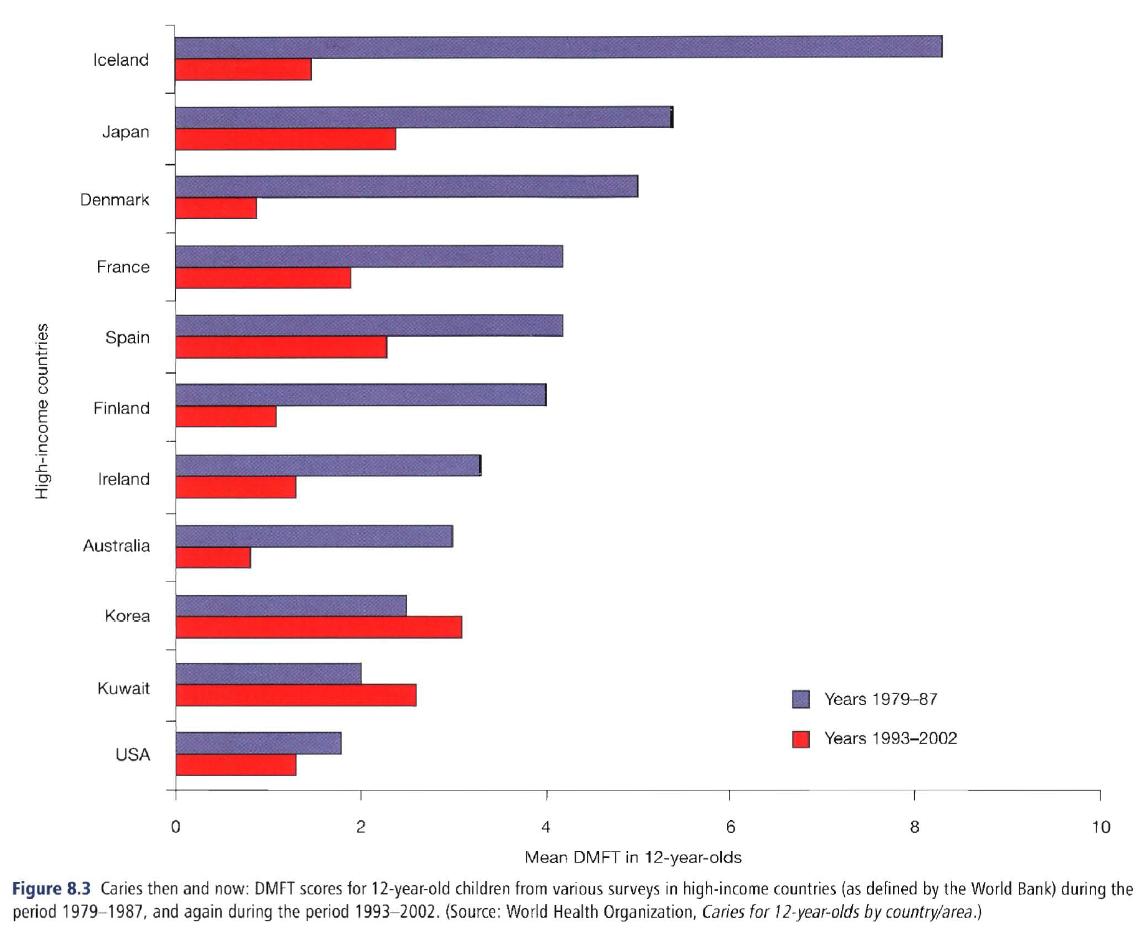

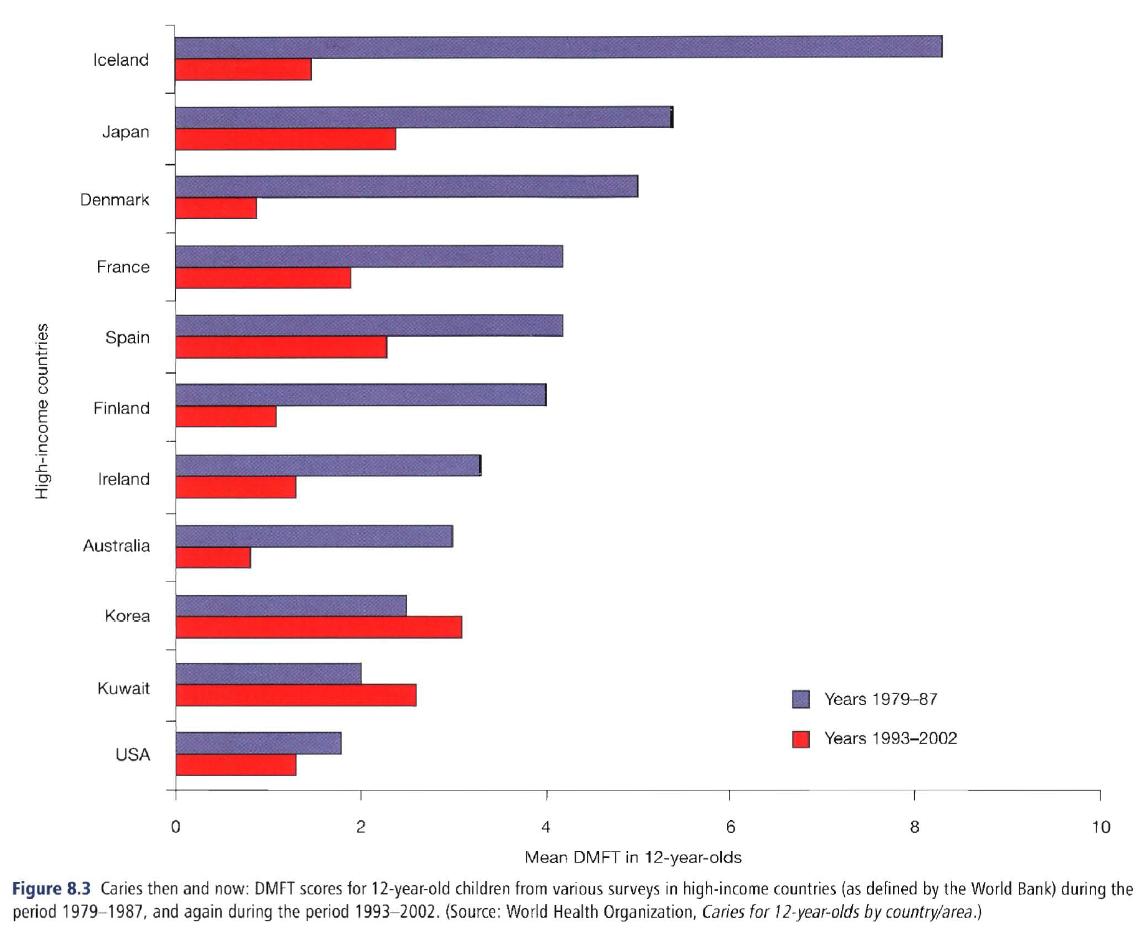

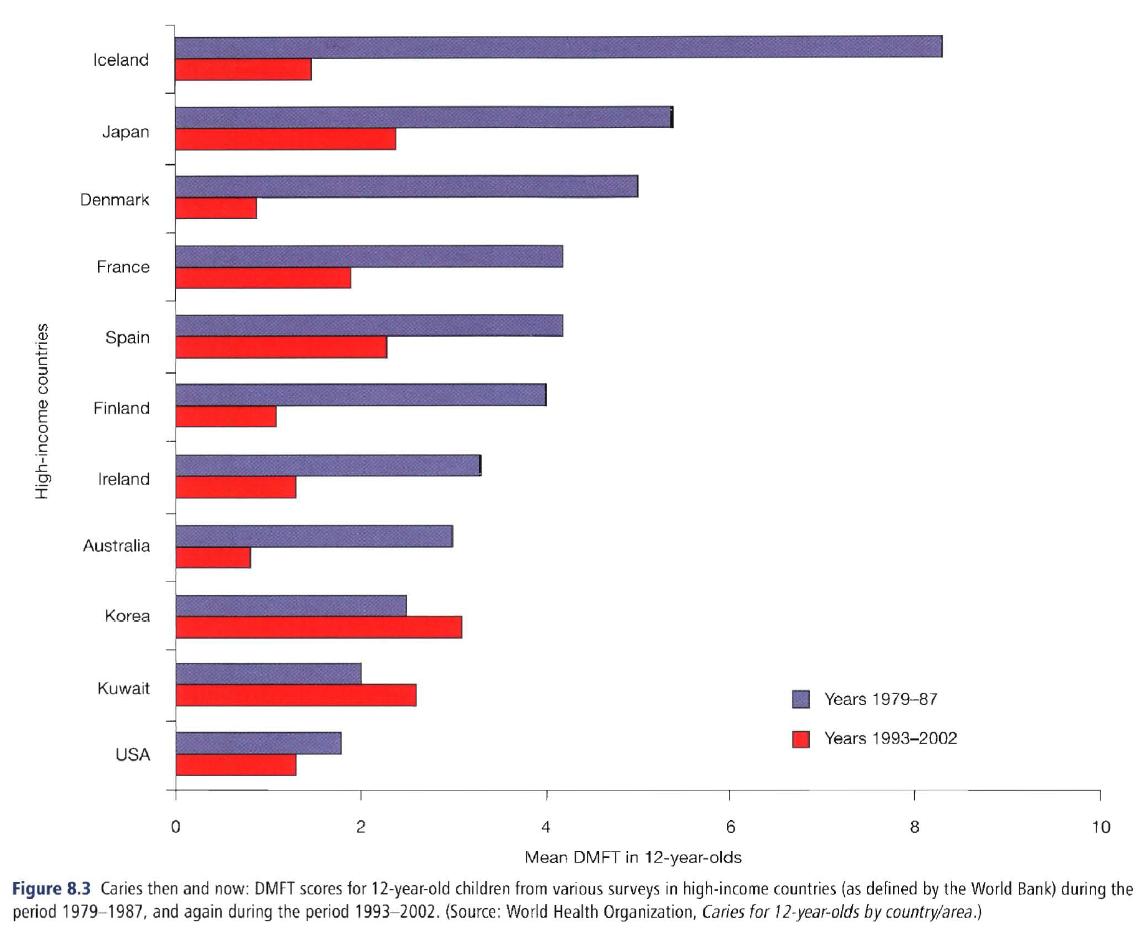

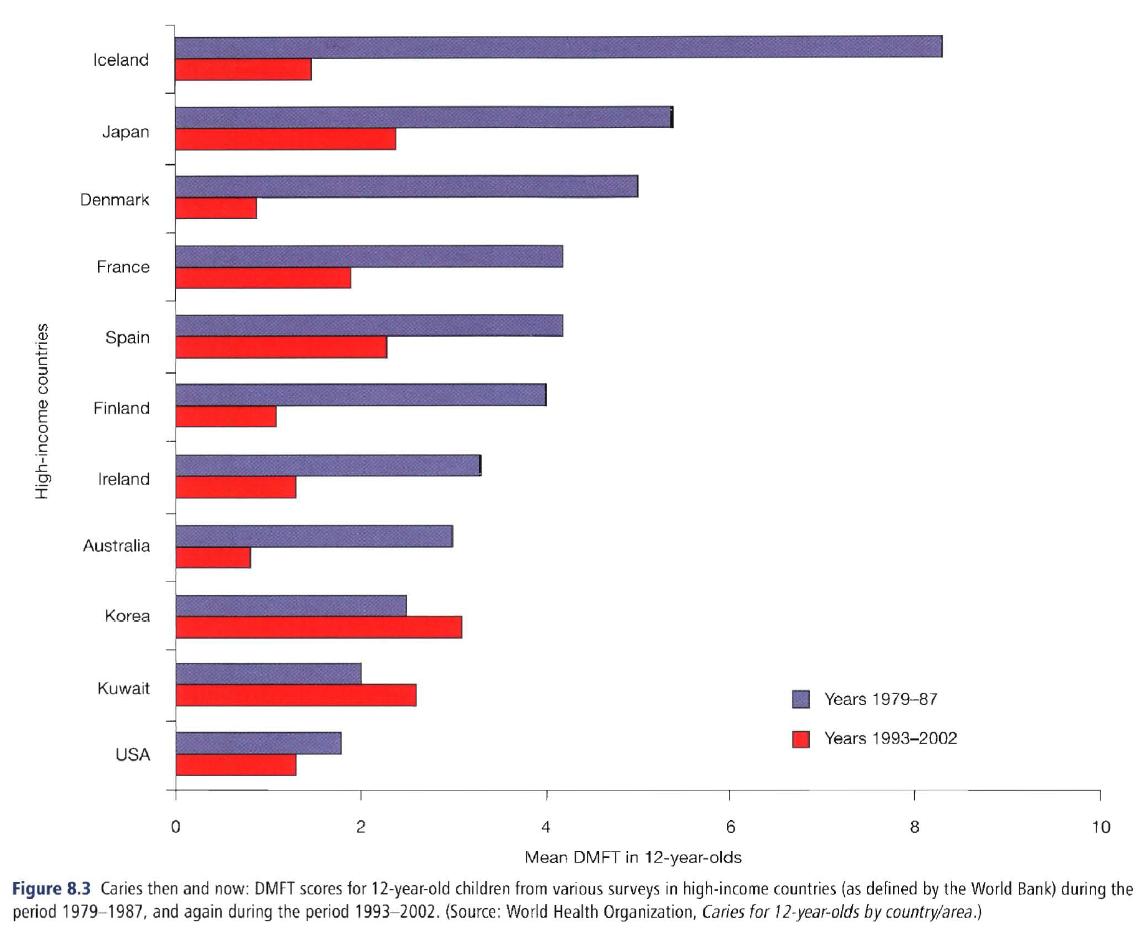

Figure 8.3 uses figures from the Global Oral Health Data Bank and from the World Bank to show the trends in DMFT scores in 11 high-income countries from 1979-1987 and from 1993-2002.

Figure 8.3 uses figures from the Global Oral Health Data Bank and from the World Bank to show the trends in DMFT scores in 11 high-income countries from 1979-1987 and from 1993-2002.

Figure 8.3は、世界銀行のGlobal Oral Health Data Bankの数字から、1979-1987年と1993-2002年の11の高所得国家におけるDMFTスコアの傾向を示している。

For most of these countries the decline in caries levels has been substantial, but again it is not universal because both Korea and Kuwait have seen a rise in DMFT scores.

これらの国のほとんどでは、齲蝕水準の大規模な減少が生じているが、やはりこれも普遍的なものではなく、KoreaとKuwaitではDMFTスコアの増加がみられる。[2010.2.16]

This could be because preventive measures have lagged behind rapidly growing affluence (and hence easier access to cariogenic diets) in these countries.

これは、これらの国での豊かさの急速な広まり(と、それによる炭水化物摂取の増加)の背後で、予防対策が遅れを取っていることにある。

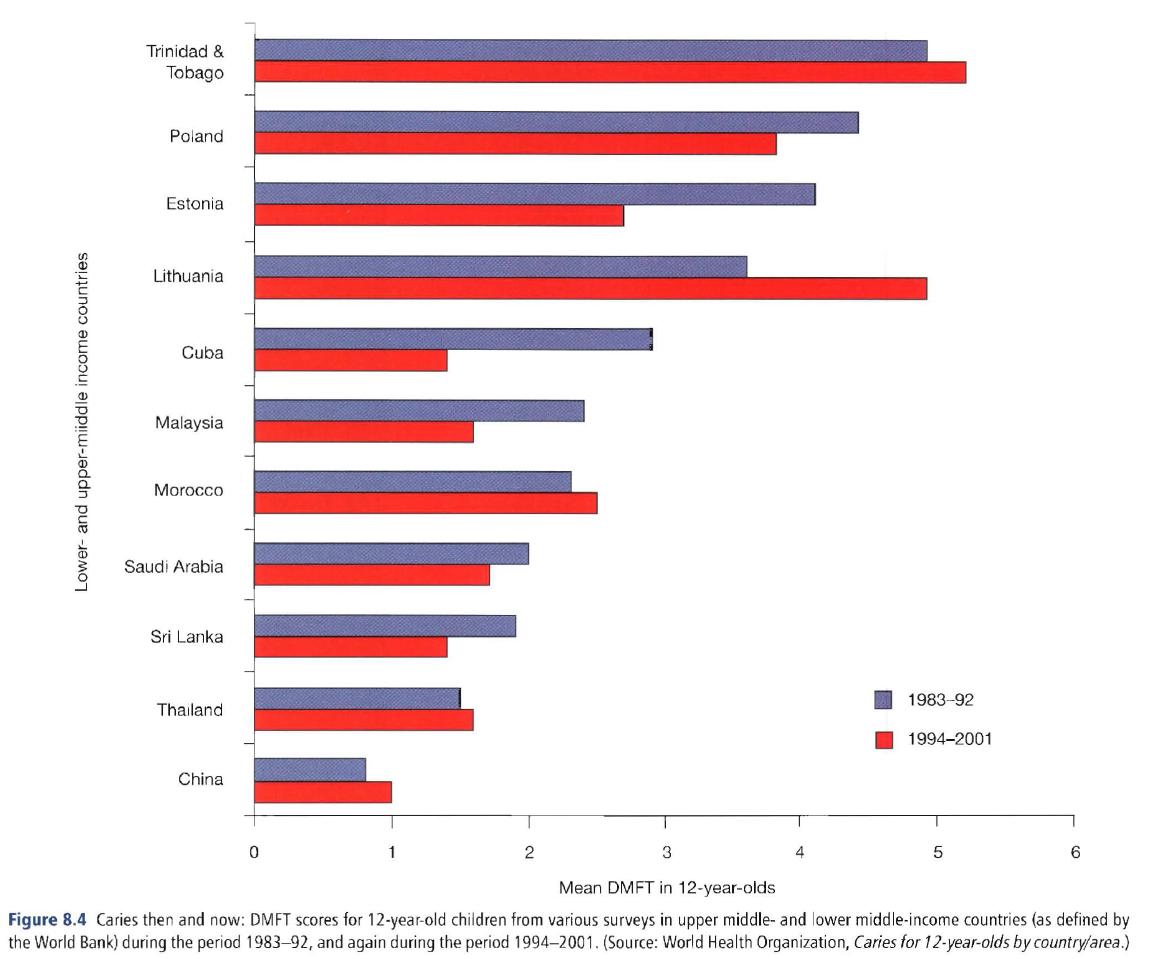

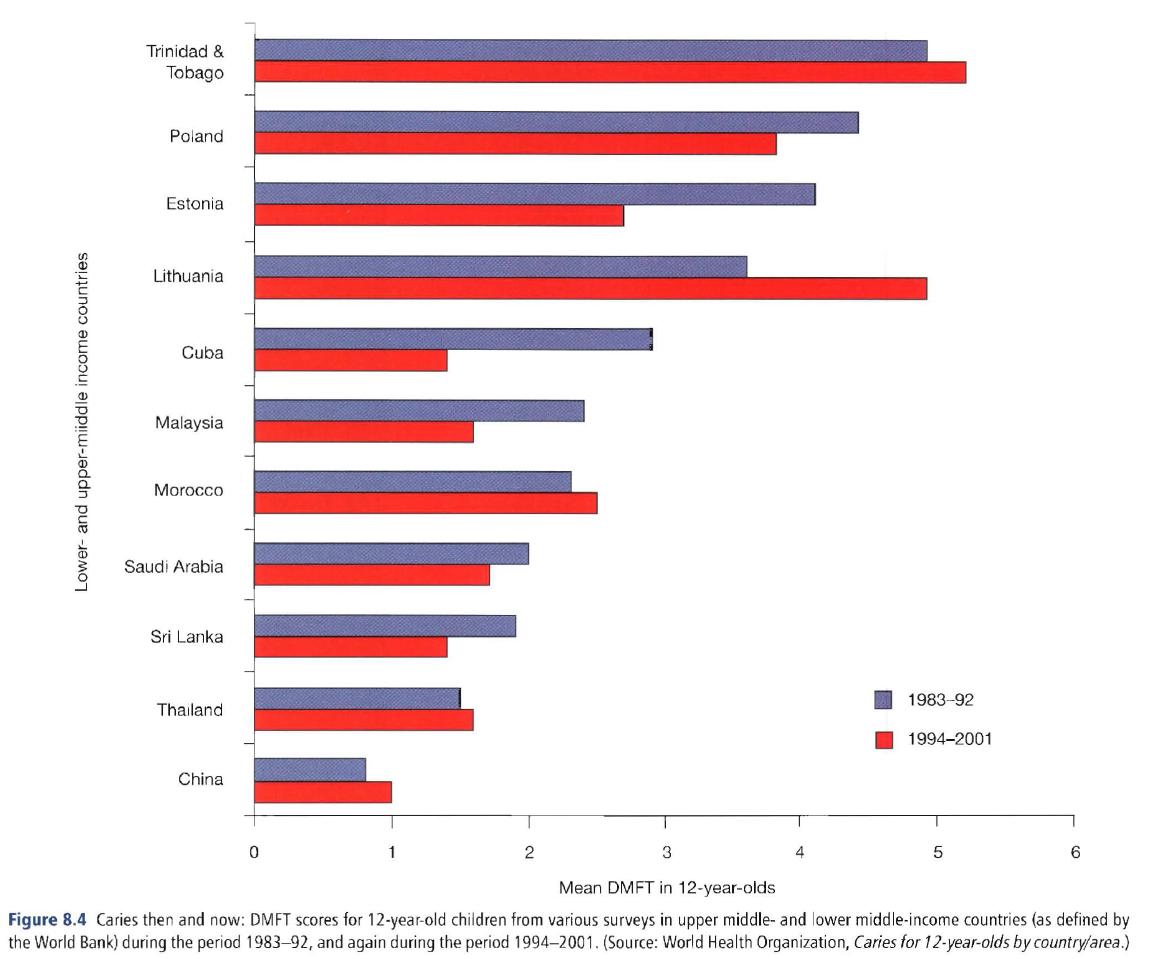

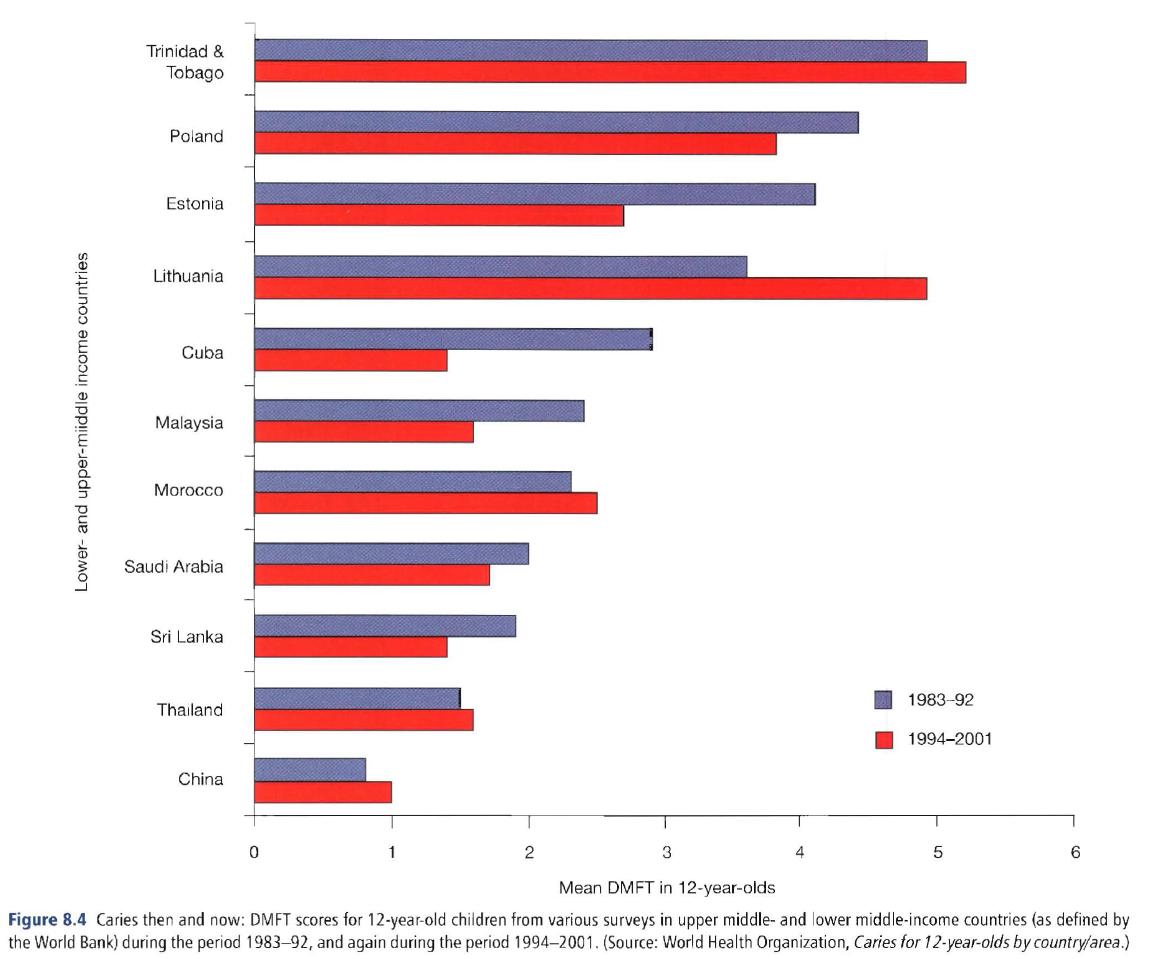

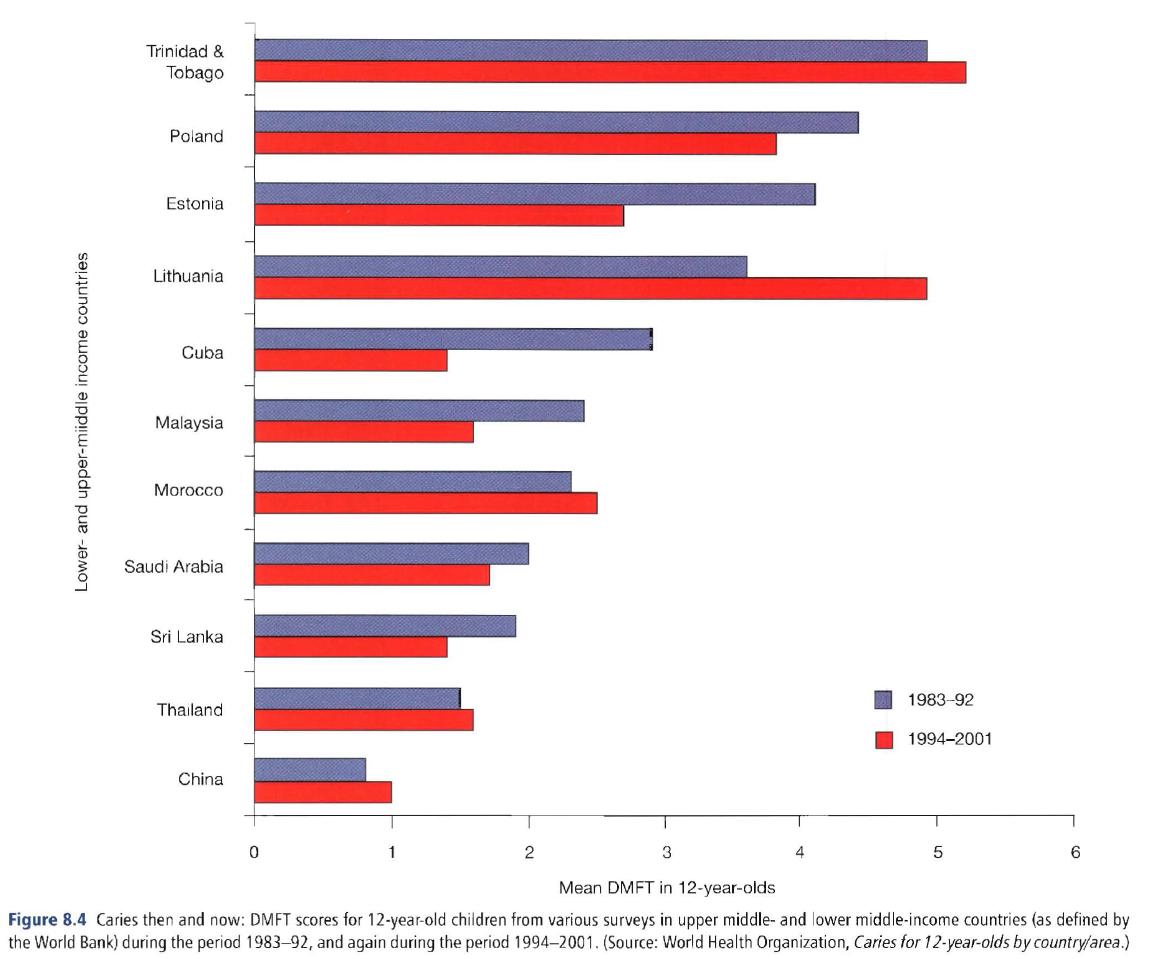

Figure 8.4 shows the same display for selected upper middle- and lower middle-income countries, those without the same resources as the countries in Fig. 8.3, and here the pattern is different.

Figure 8.4 shows the same display for selected upper middle- and lower middle-income countries, those without the same resources as the countries in Fig. 8.3, and here the pattern is different.

Figure 8.4は、中高所得国家と中低所得国家を選び、DMFTスコアをあらわしているが、傾向に違いのあることがお分かりだろうか。

Only Cuba, which has had a school dental service for years, and Estonia, where caries levels were very high, have shown a substantial drop in caries patterns over the past 20-25 years.

数年にわたり学校歯科医療を行っているCuba、そして齲蝕水準の高いEstoniaでは、この20-25年の間に、齲蝕傾向の大きな減少が見られる。[Cubaは上から5番目、Estoniaは上から3番目]

Of the others, four have shown a minor decline, and four have had an increase.

そのほかの国では、4ヶ国に、わずかな減少が、5ヶ国には上昇が認められる。

They do show a pattern: nations with better developed public health prevention programs generally have shown most success with caries reduction.

これには、ある傾向が見られる。公衆衛生予防計画が進んでいる国ほど、齲蝕減少に成功しているのである。[...prublic health prevention programs...ね][2010.2.17]

However, distinct differences in caries experience exist from one country to another and from region to region within a country.

しかし、国ごと、そして国内の地域ごとにも、齲蝕経験の格差は存在している。[2010.2.19]

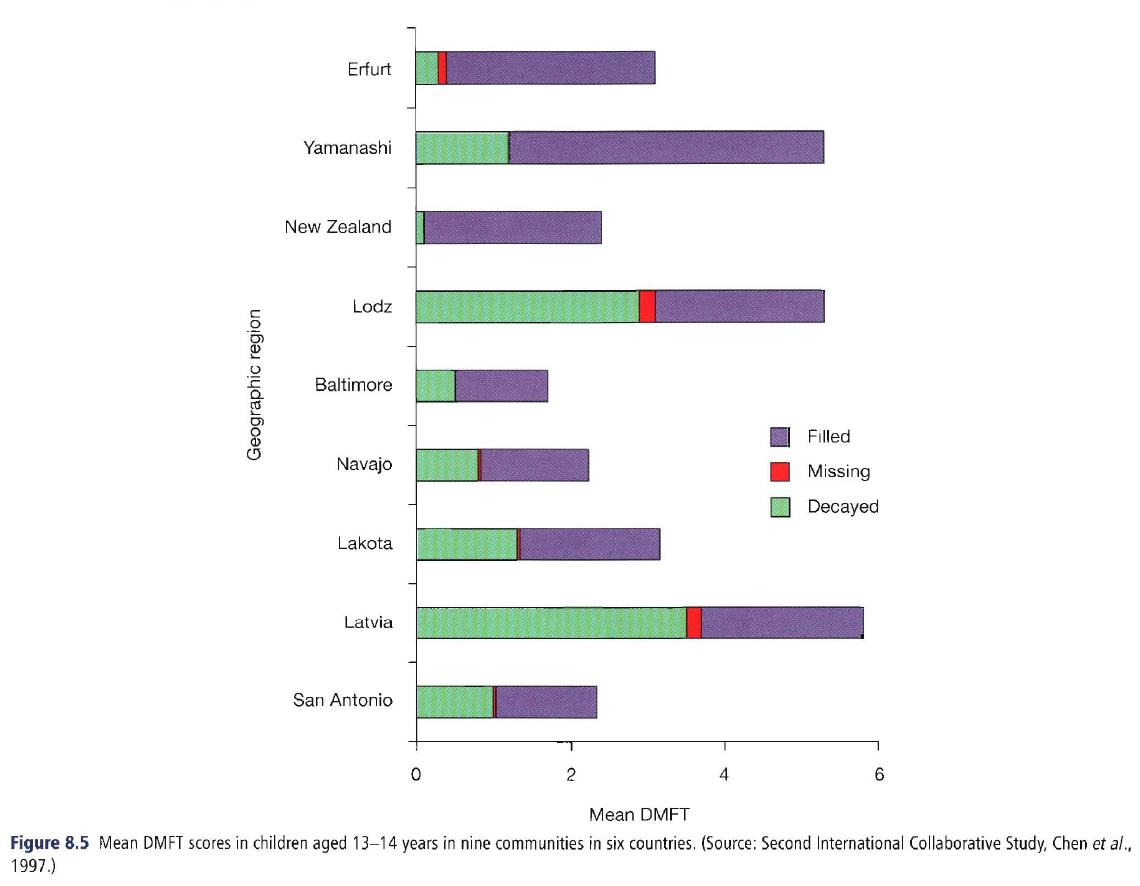

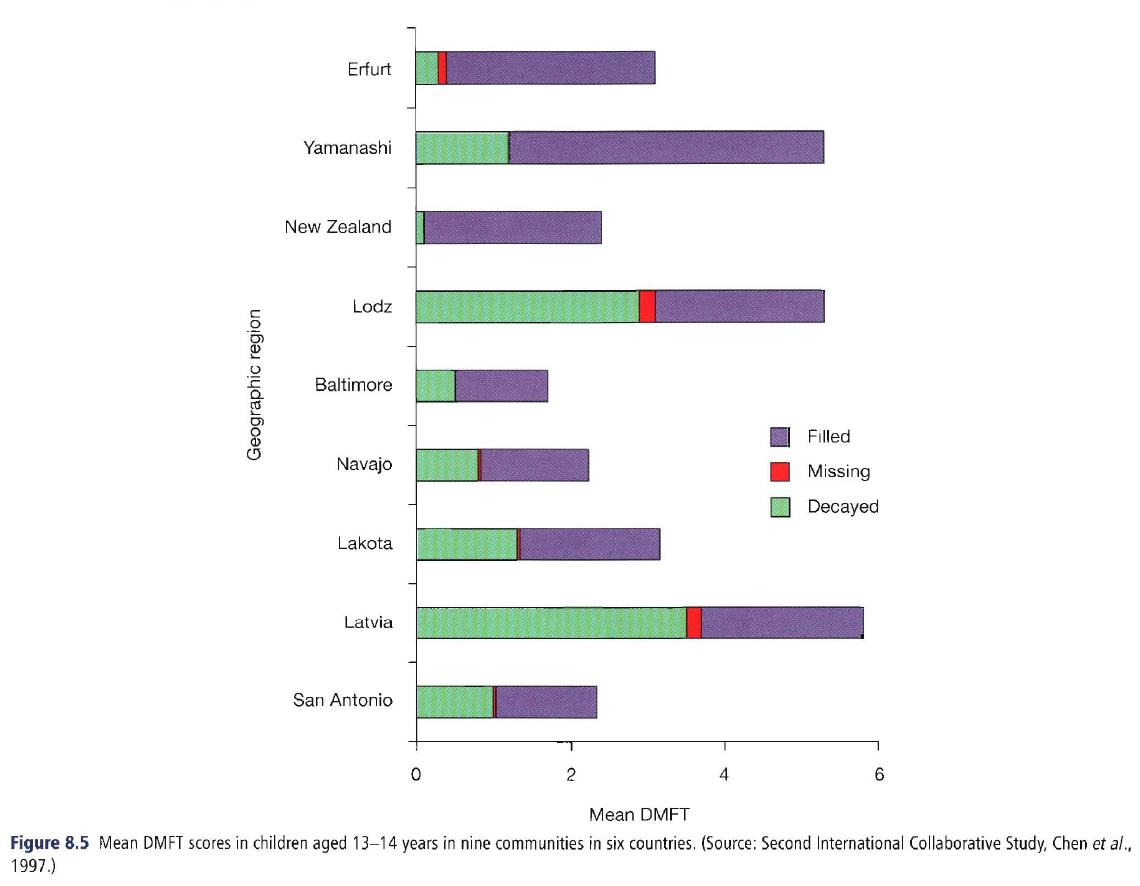

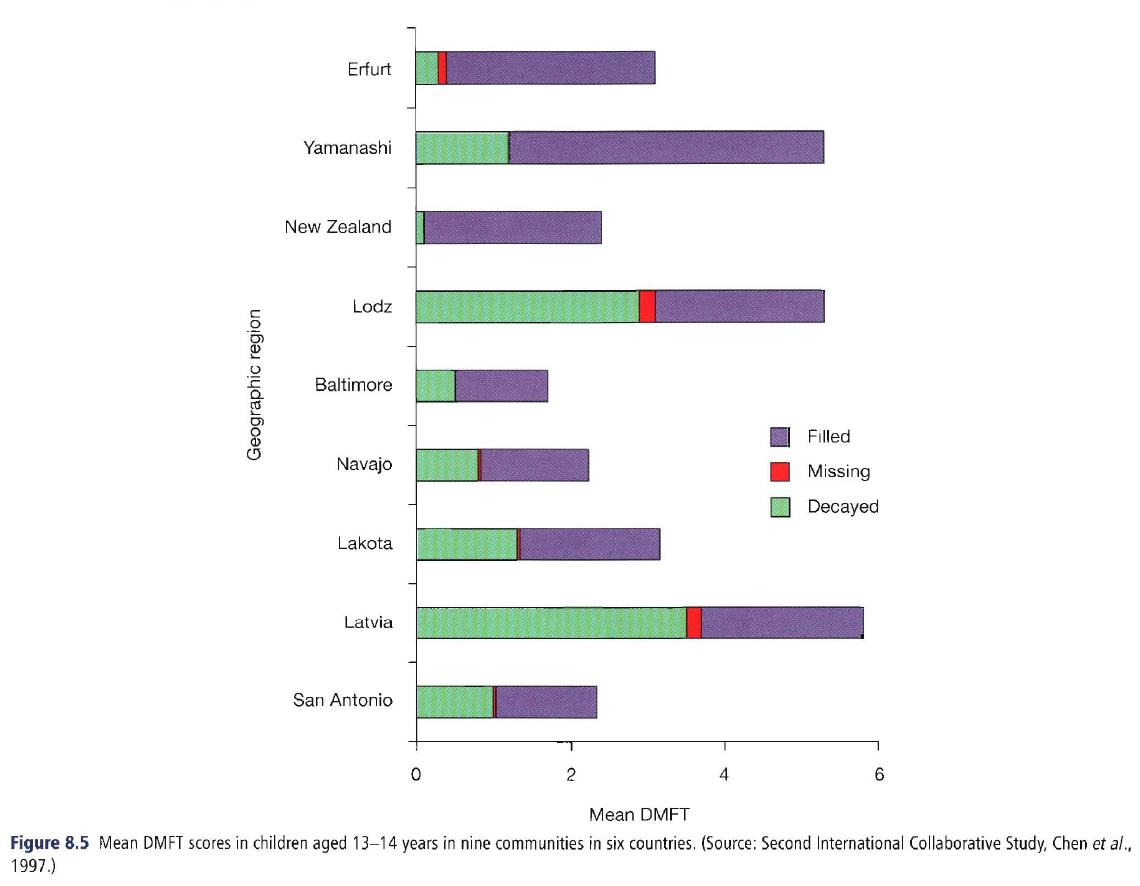

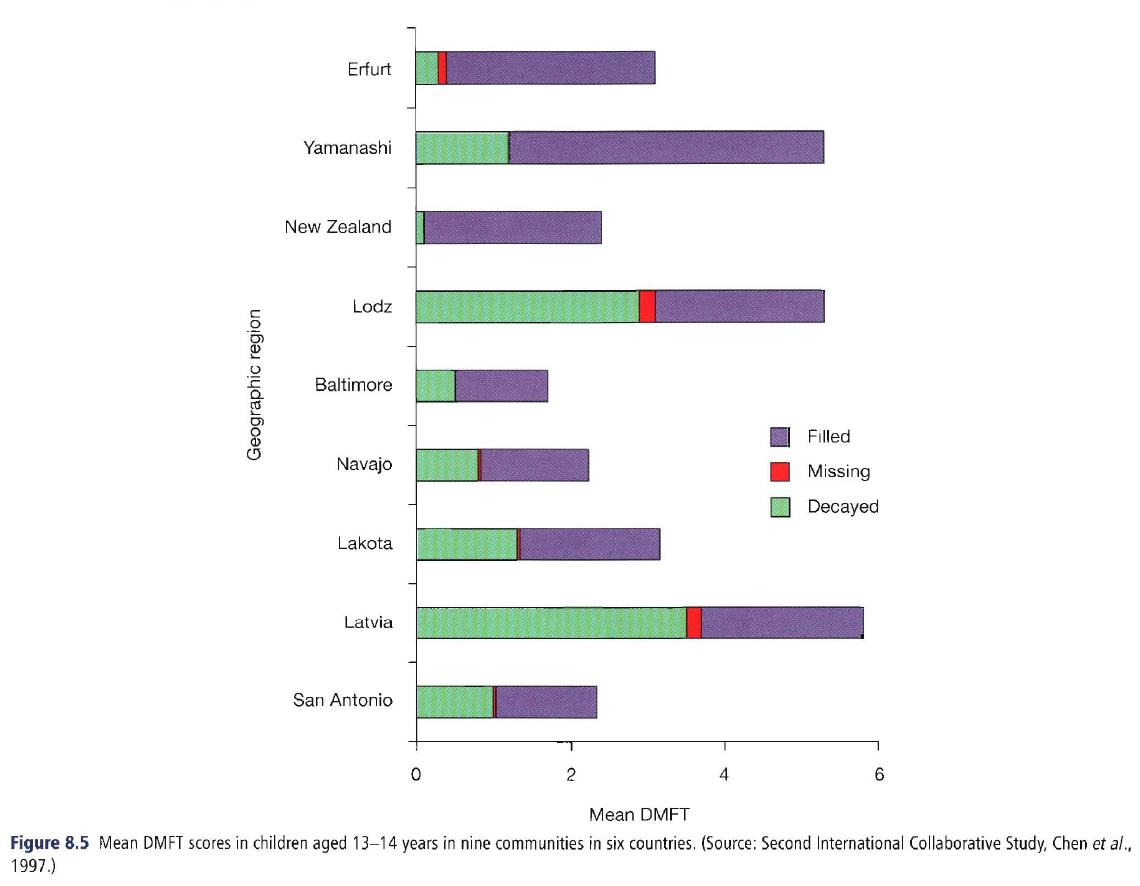

Intercountry differences are illustrated by the results of the second International Collaborative Study (ICS II) in the 1990s (Chen et al., 1997), shown in Fig. 8.5.

Intercountry differences are illustrated by the results of the second International Collaborative Study (ICS II) in the 1990s (Chen et al., 1997), shown in Fig. 8.5.

Fig. 8.5には、国内格差の実態を、1990年代の第2回国際協力研究 (ICS II) に基づき示した (Chen et al., 1997)。

The 13-14-year-old children examined were from selected communities rather than from nationally representative population samples, so there is a possibility of selection bias in these data.

診査された13-14歳児は、国を代表する標本ではなく、ある地域からの標本なので、これらの資料にはセレクションバイアスがあるかもしれない。

The highest caries levels are seen in Eastern European countries and Japan.

もっとも齲蝕水準が高いのは、東欧諸国と日本である。

Differences in caries experience between countries are not always easy to explain, but can often be seen to stem from sample selection and variable caries criteria.

齲蝕経験の国家間の格差は、簡単に説明できるわけではないが、標本抽出と齲蝕の基準のばらつきに起因するものと考えられる。

Secular variations in caries extent and severity

齲蝕の広がりと重症度の経年的ばらつき

Several reports from both national data and local surveys by the early 1980s suggested that the previously high DMF scores in high-income countries were diminishing (Hunter, 1979; McEniery & Davies, 1979; Sardo Infirri & Barmes, 1979; Hugoson et al., 1980; Anderson et al., 1981; Glass, 1981; Hughes & Rozier, 1981; Bryan et al., 1982; Fejerskovet al., 1982; Stookey et al., 1985).

1980年代初頭の全国資料と地方の調査の両方が、高所得国家のDMFスコアは、以前より低下していることを示唆していた (Hunter, 1979; McEniery & Davies, 1979; Sardo Infirri & Barmes, 1979; Hugoson et al., 1980; Anderson et al., 1981; Glass, 1981; Hughes & Rozier, 1981; Bryan et al., 1982; Fejerskovet al., 1982; Stookey et al., 1985)。

In the USA, as one example, this decline in caries prevalence and severity was confirmed by results from the National Dental Caries Prevalence Survey in US School Children of 1979/80 (US Public Health Service, NIDR, 1981).

USAでの1つの例としては、1979/80年のUS学童齲蝕有病割合全国調査の結果により、齲蝕の有病割合と重症度が低下していることが確認されている (US Public Health Service, NIDR, 1981)。

This survey found that mean DMF scores among children aged 5-17 years were some 32% lower than those in the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of 1971-1974 (US Public Health Service, NCHS, 1981).

この調査は、5-17歳児の平均DMFスコアは、1971-81年のNHNES I(第1回保健栄養全国調査)よりも32%低くなったことを示していた (US Public Health Service, NCHS, 1981)。

The next national survey of US schoolchildren in 1986/87 found that the decline was continuing (US Public Health Service, NlDR, 1989), with mean DMF scores for 5-17-year-olds again 36% lower than those from seven years earlier, and this trend continued through the national survey of 1988-1994 (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1997).

1986/1987年のUS学童全国調査は、この減少傾向が継続していることを示し (US Public Health Service, NlDR, 1989)、5-17歳児の平均DMFスコアは、7年前と比較して、さらに36%低下し、この傾向は1988-1994年の全国調査でも継続していた (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1997)。

P130

The caries decline in the permanent dentition continues to the present day, and is apparent in just about all of the high-income countries.

永久歯にみられる、この齲蝕減少傾向は、今日まで継続しており、ほぼすべての高所得国家に見られている。

As an example from the USA, Fig. 8.6 shows the average DMFT scores among children of three different age groups in the two most recent national surveys, only some 8-11 years apart.

As an example from the USA, Fig. 8.6 shows the average DMFT scores among children of three different age groups in the two most recent national surveys, only some 8-11 years apart.

このUSAの例として、Fig. 8.6は(8-11年間隔の)直近2回の全国調査における3つの年代の児童の平均DMFスコアを示す。

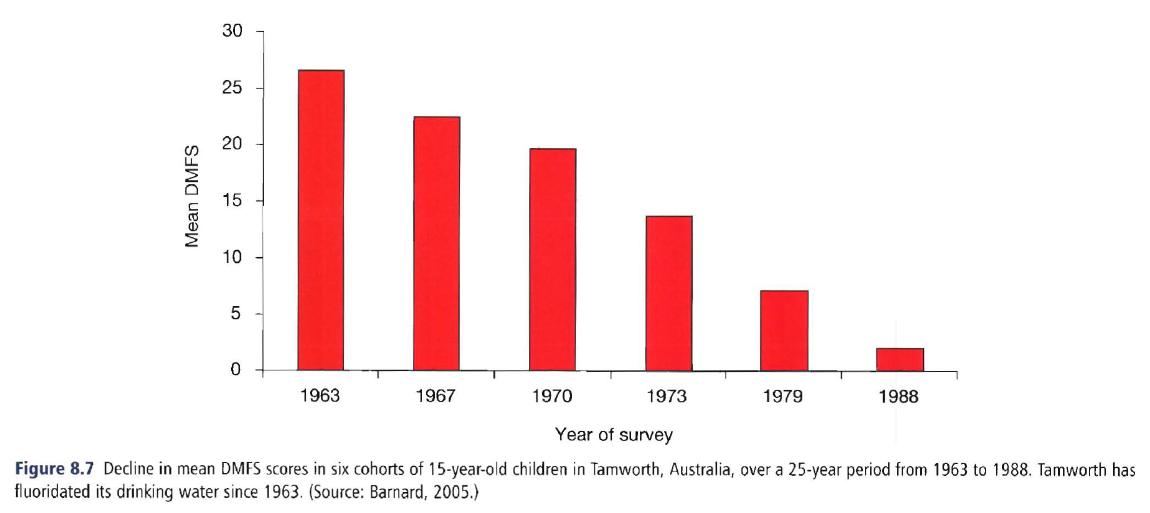

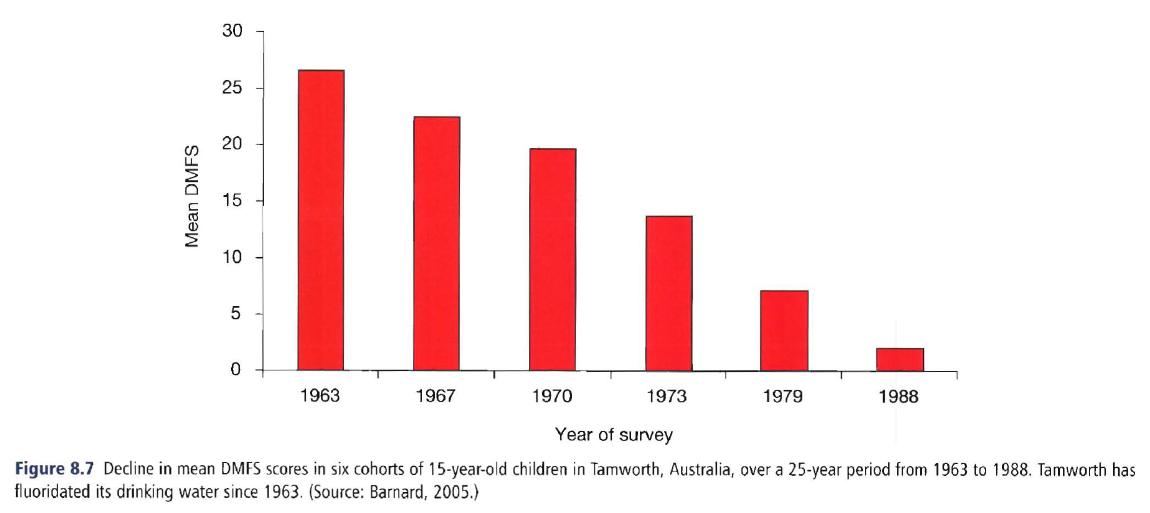

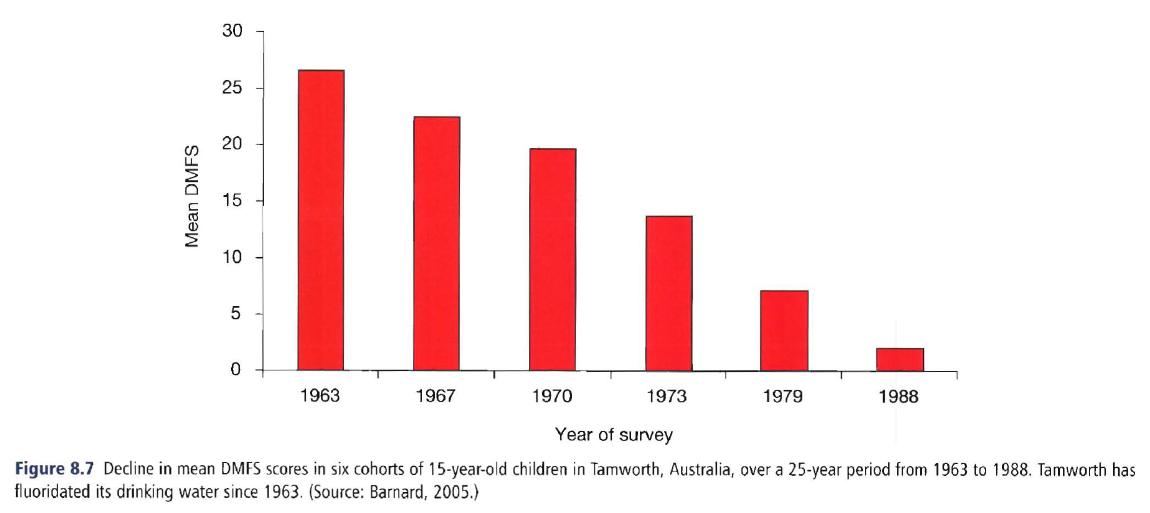

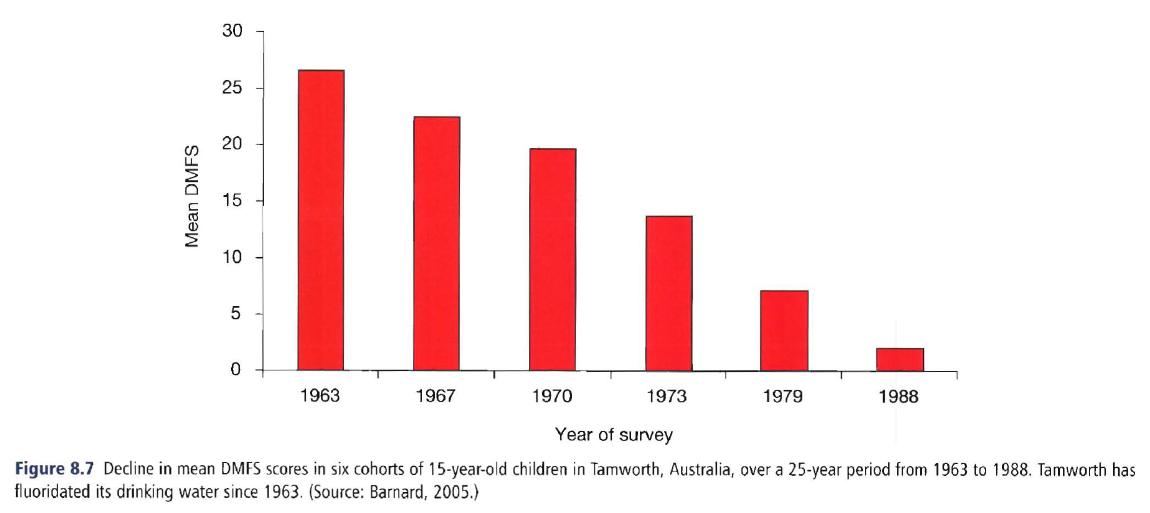

Another example comes from Australia, where the city of Tamworth was the site of a series of dental surveys over a period of 25 years.

Australiaから、もう1つの例がある。Tamworthの街は25年間隔で歯の調査を行っている。

The first survey was a baseline for Tamworth’s commencement of water fluoridation in 1963, and the surveys of school children continued periodically until 1988.

この調査は、水道水フッ化物添加を開始した1963年をベースラインとしており、1988年まで定期的に学童の調査を行っていた。

Figure 8.7, in which the data are all for 15-year-old children, shows the trend of constantly diminishing caries experience in Tamworth over a period of increasing use of fluoride.

Figure 8.7, in which the data are all for 15-year-old children, shows the trend of constantly diminishing caries experience in Tamworth over a period of increasing use of fluoride.

Figure 8.7は、15歳児の資料であり、Tamworthでは、フッ化物応用が進んだ時期に、齲蝕経験が減少し続けた傾向が示されている。

The DMF index, as described above, is a measure of average caries severity in terms of the number of teeth affected by caries.

DMF指数は、以上に示したように、齲蝕に侵された歯の数という意味で、齲蝕の平均的重症度の指標である。

Another measure, more readily understood by other health professionals and the public, is prevalence, defined as the number of disease cases at a given time (while incidence is the number of new disease cases over a specified time).

医師や一般の人々により容易に理解される指標は、有病数である。これはある1時点における疾病の数として定義される。(これに対して、発生数は、特定の期間に新たに発生した疾病の数である。)[この定義は、疫学事典によればpoint prevalenceに近い]

It is shown in Chapter 9 that caries is a process, thus making it difficult to say exactly when caries starts.

Chapter 9に示すように、齲蝕はプロセスであり、厳密に齲蝕がはじまった時点を特定するのは、容易ではない。

Chapter 9 also makes the point that there really is no such thing as ‘caries free’.

Chapter 9では、実際に‘齲蝕なし’なんぞ、ありえない、としている。

However, public health workers need to be able to identify those children who need operative or non-operative treatment, and a convenient marker for that is ‘free of obvious caries’, i.e. open cavities or tissue loss in fissures that are readily detectible.

しかし、公衆衛生担当者は、外科的治療や非外科的な治療を必要とする小児を特定する必要があり、‘明らかな齲蝕(容易に検出可能な開いた窩洞や裂溝の組織欠損)はない’というのは、その便利な指標である。[2010.2.20]

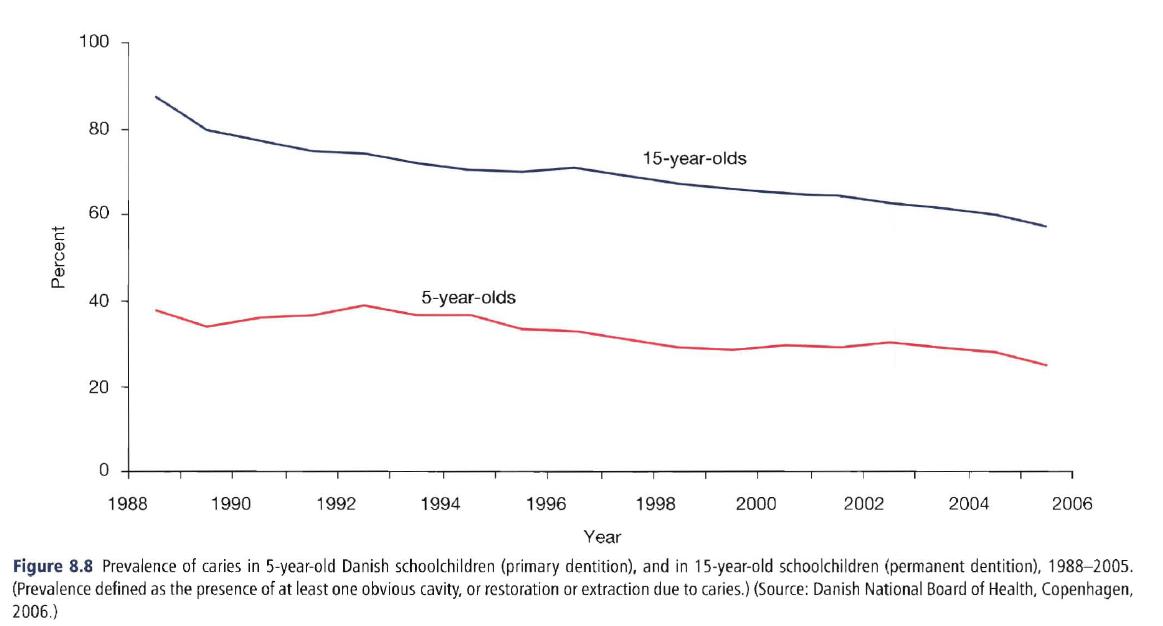

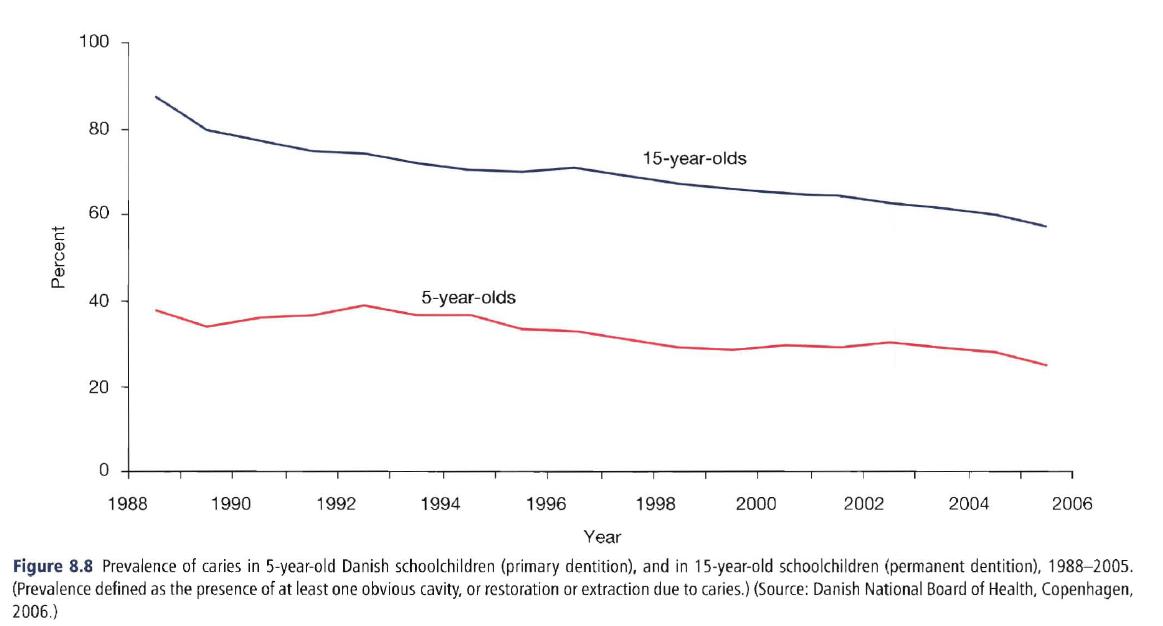

So ‘prevalence of caries’, as the term is used in public health surveillance and programming, means the proportion of a population that has at least one obvious lesion (or a restoration or extraction due to caries).

だから、‘齲蝕の有病割合’は、公衆衛生調査と計画で使われるときには、最低でも1つの明らかな病巣(あるいは、齲蝕による修復か抜歯)のある人の割合を意味する。[疫学事典でも説明されますが、proportion割合とrate率は、異なる定義が与えられていますので、区別が必要です]

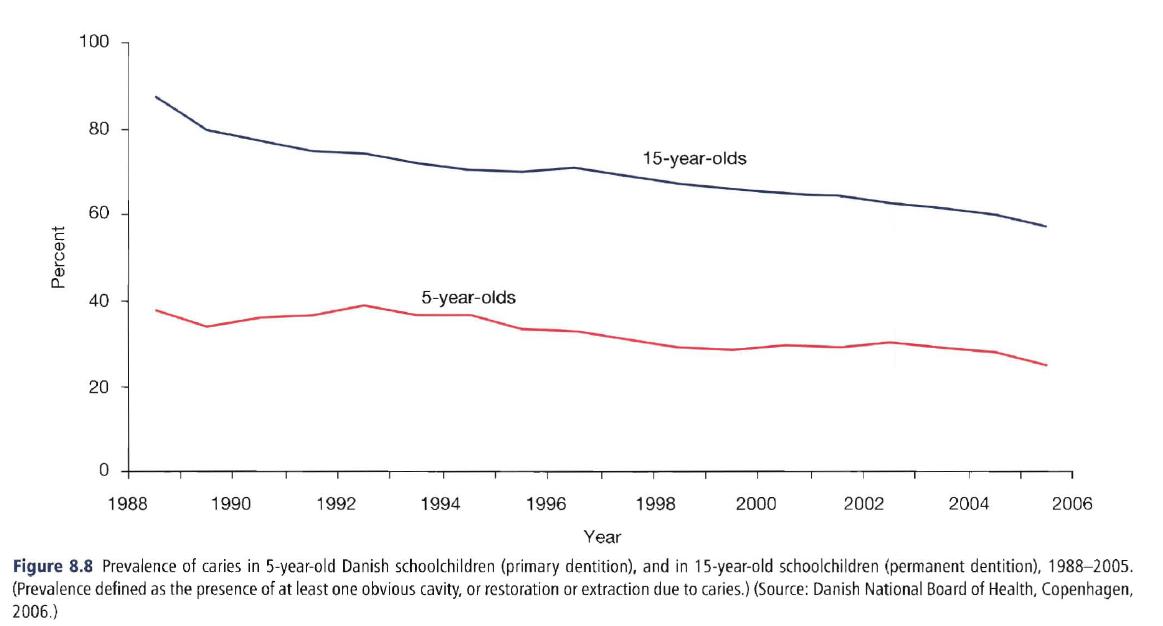

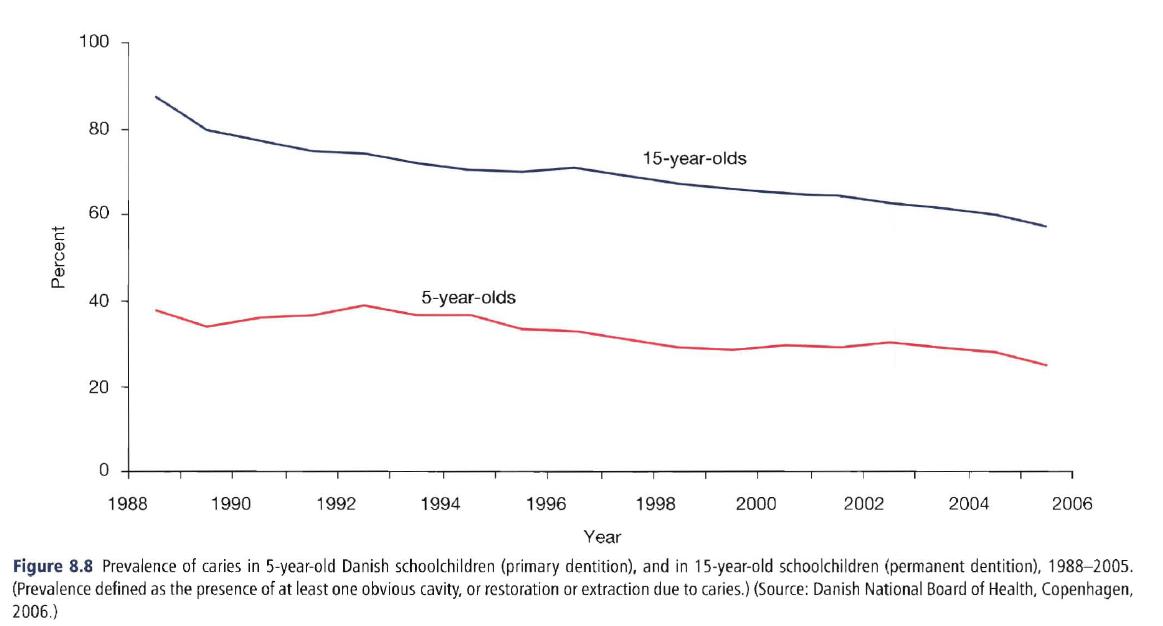

Looking at such data from the Danish School Dental Service over the period from 1988 to 2005 (Fig. 8.8), it can be seen that the prevalence of caries has dropped steadily over the years, both in the primary dentition (5-year-olds) and in the permanent dentition (15-year-olds).

Looking at such data from the Danish School Dental Service over the period from 1988 to 2005 (Fig. 8.8), it can be seen that the prevalence of caries has dropped steadily over the years, both in the primary dentition (5-year-olds) and in the permanent dentition (15-year-olds).

1988-2005年のDanish School Dental Serviceの資料 (Fig. 8.8) を見ると、乳歯(5歳児)と永久歯(15歳児)の両方で、齲蝕有病割合は年を追って低下してきている。

P131

The seemingly sudden decline in caries among children in high-income nations (which was perhaps not all that sudden because there are data to suggest that it might have started in the 1960s: Fejerskov et al., 1982; Burt, 1985) was documented at a 1982 conference in Boston, the proceedings of which were published in a special issue of the Journal of Dental Research in November 1982.

高所得国家における小児齲蝕の、一見、突然の減少(1960年代から始まっていることを示唆する資料があるので、それほど突然でもないのだが: Fejerskov et al., 1982; Burt, 1985)は、1982年11月のJournal of Detnal Researchのspecial issueで公開する過程で、同年のBoston合意会議にて明らかにされた。

The decline in caries in the permanent dentition among children of the high-income nations has continued since then (Kumar et al., 1991; Bjarnason et al., 1993; Athanassouli et al., 1994; Downer, 1994; Spencer, 1994; Marthaler et al., 1996; Truin et al., 1998; Carvalho et al., 2001).

高所得国家の小児の永久歯の齲蝕の減少は、当時から現在まで継続中である (Kumar et al., 1991; Bjarnason et al., 1993; Athanassouli et al., 1994; Downer, 1994; Spencer, 1994; Marthaler et al., 1996; Truin et al., 1998; Carvalho et al., 2001)。

The main caries problem in the high-income countries today is not so much overall caries levels, but rather the disparities in disease experience and treatment between different socioeconomic and racial/ethnic groups.

今日では、高所得国家における齲蝕は、齲蝕水準ではなく、SESや人種による、疾病経験や治療の格差が、主な課題となっている。[2010.2.21]

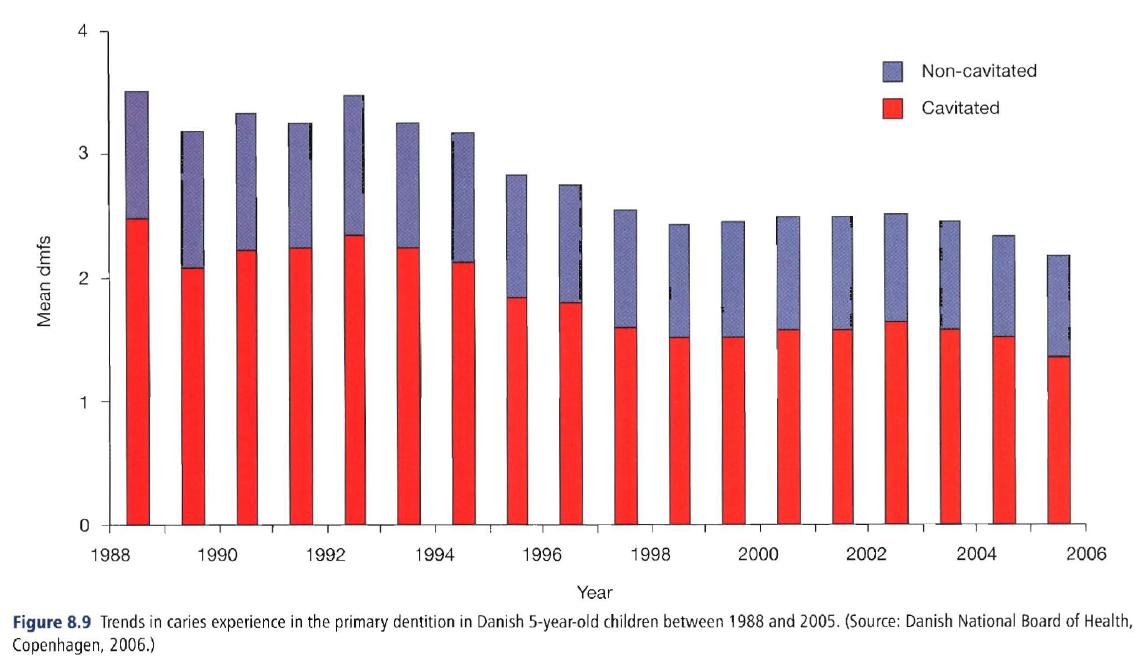

Regarding caries trends in the primary dentition, there is evidence that the caries decline paralleled that seen in the permanent dentition until around the late 1980s to early1990s, when the decline seemed to level out (Hargreaveset al., 1987; Brown et al., 1995; Kaste et al., 1996; Marthaleret al., 1996; Poulsen, 1996; Speechley & Johnston, 1996; Truin et al., 1998; Poulsen & Scheutz, 1999).

1980年代の終わりから1990年代初期にかけて永久歯に見られたような齲蝕の減少の停滞は、乳歯の齲蝕に関しても同様である、という検証がある (Hargreaveset al., 1987; Brown et al., 1995; Kaste et al., 1996; Marthaleret al., 1996; Poulsen, 1996; Speechley & Johnston, 1996; Truin et al., 1998; Poulsen & Scheutz, 1999)。

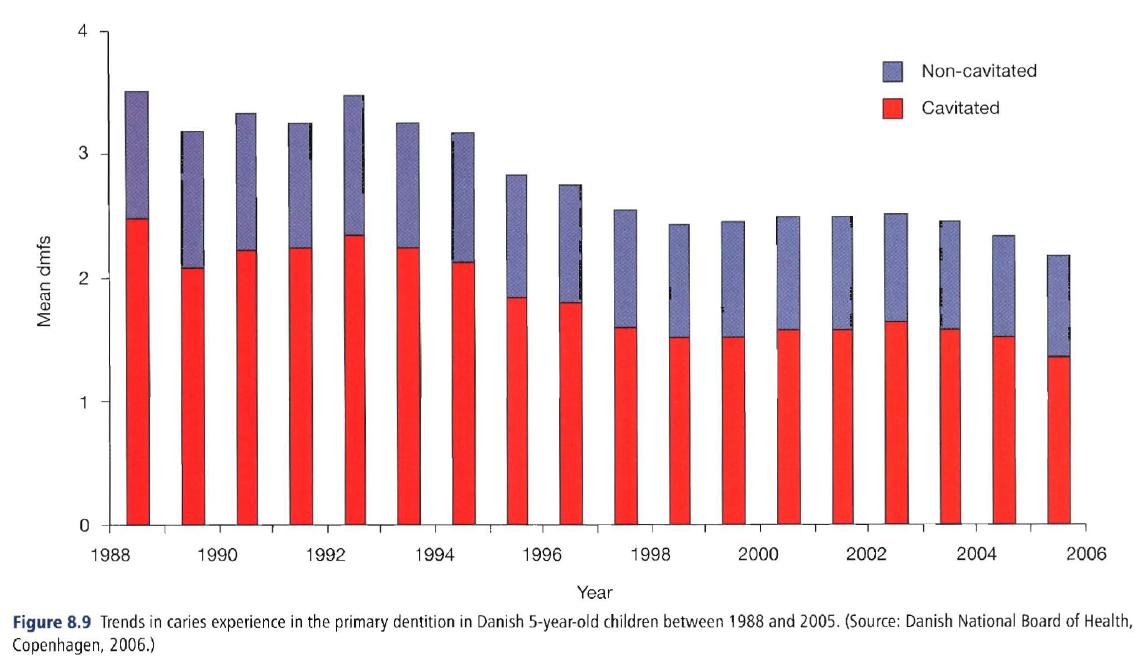

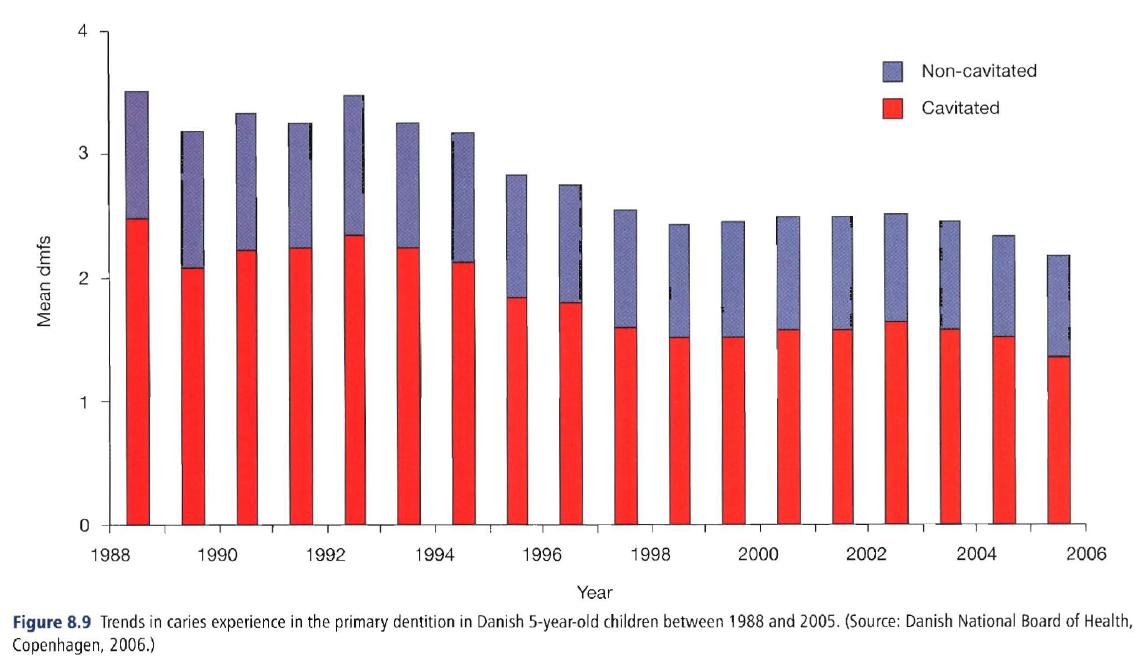

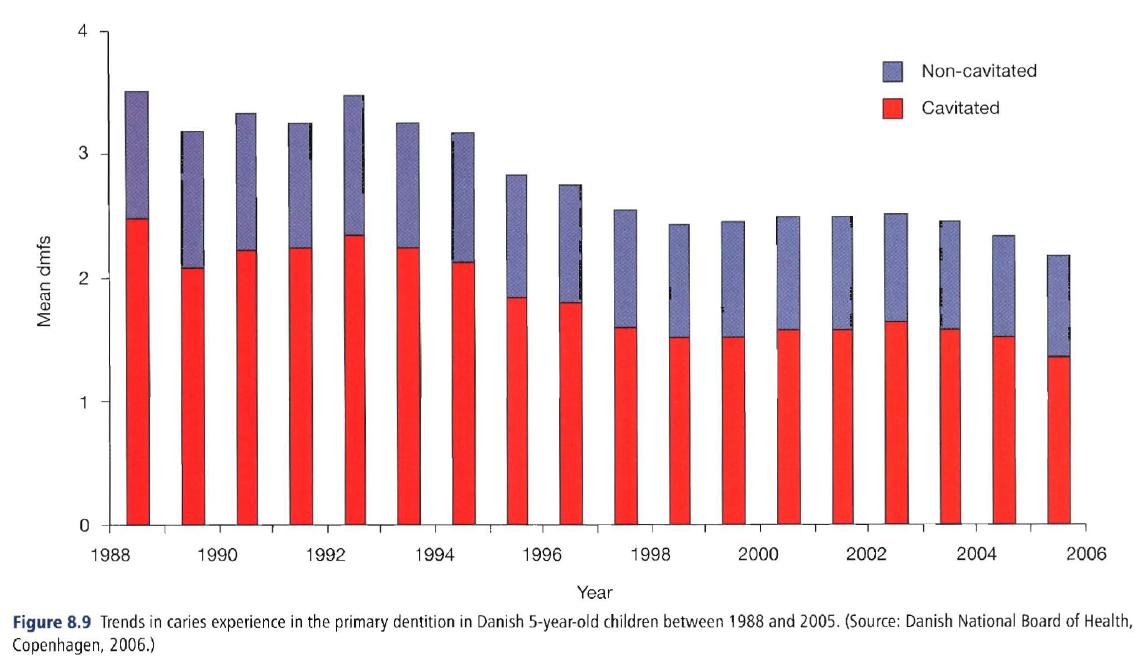

Data from the Danish School Dental Service shown in Fig. 8.9 and covering the period from 1988 to 2005, however, suggest that another decline was evident in the early 1990s, followed by a plateauing from then to the present.

Data from the Danish School Dental Service shown in Fig. 8.9 and covering the period from 1988 to 2005, however, suggest that another decline was evident in the early 1990s, followed by a plateauing from then to the present.

しかし、Figure 8.9に示した、1988-2005年を対象にしたDanish School Dental Serviceの資料は、1990年代初期の減少に続いて停滞が生じていることを示唆している。

(Figure 8.9 also demonstrates again how including or excluding non-cavitated lesions in the recording affects the outcome.)

(Figure 8.9は、記録に齲窩のない病巣を含むかどうかが結果にもたらす影響についても、示している。)

P132

P133

The reduction in caries has not occurred evenly across all kinds of tooth surfaces, for it has been proportionately greater in free smooth surfaces and proximal surfaces than in pit-and-fissure surfaces (Bohannon, 1983; Stamm, 1984).

齲蝕の減少は、あらゆる歯面に等しく生じるのではない。平滑面と隣接面に生じた減少は、小窩裂溝に生じた減少よりも大きい (Bohannon, 1983; Stamm, 1984)。

In a 3-year longitudinal study in Michigan in the early 1980s, 81% of all new lesions were on occlusal surfaces and in the pits and fissures of buccal and lingual molar surfaces, with no lesions at all on free smooth surfaces (Burt et al.,1988).

1980年代初期のMichganの3年間の縦断研究では、咬合面の新たなる齲蝕病巣の81%は、臼歯の咬合面と頬舌面の小窩裂溝に生じており、平滑面には生じていなかった (Burt et al.,1988)。[残り19%は隣接面、ということか?]

The net result is that while the total number of new carious lesions has been dropping, an increasing proportion of them is made up of pit-and-fissure lesions.

新たなる齲蝕の総数は減ったため、小窩裂溝齲蝕の割合が増えているという、結果であった。

As caries prevalence falls, the least susceptible sites (proximal and smooth surfaces) reduce by the greatest proportion, while the most susceptible sites (occlusal) reduce by the smallest proportion (McDonald & Sheiham,1992).

齲蝕有病割合は低下しているが、感受性の低い部位(隣接面と平滑面)は、齲蝕の減少が大きく、感受性の高い部位(咬合面)は、齲蝕の減少が小さい。 (McDonald & Sheiham,1992)。

History has many examples of diseases that have waxed and waned without a firm understanding of why, and caries is one of these.

歴史は、人類による確固たる理解を寄せ付けずに猛威を奮い、また衰退の途をたどる疾病のさまざまな例を見せてくれる。そして、齲蝕は、そのような疾病の1つである。

No clear reasons for the caries decline have been identified, although most researchers see the various uses of fluoride as the main reason (Bratthall et al., 1996).

齲蝕の減少の原因は明らかではないが、多くの研究者は、主たる原因は、さまざまなフッ化物応用にあると、にらんでいる。

However, fluoride alone does not explain more than about 50% of the reduction (Marthaler et al., 1996), and we still do not have a clear understanding of the relative strength of caries risk factors.

しかし、フッ化物は、齲蝕減少の50%程度を説明するに過ぎず (Marthaler et al., 1996)、私たちは、齲蝕のリスクファクターの相対的重要性については、よく理解していない。

Sugar consumption, in the USA at least, has increased rather than diminished, and there is no good evidence concerning the roles of better oral hygiene, changes in the bacterial ecology of the oral cavity and the widespread use of pediatric antibiotics on oral bacteria.

少なくともUSAでは、砂糖消費は勢いを増しており、また、口内衛生、口内細菌叢の変化、口内細菌への小児抗菌薬の広範な使用のはたらきについての検証は、ない。[2010.2.22]

Many see a likely impact, though as yet unquantified, from raised living standards that come with indoor plumbing, and elevated social norms concerning laundry, personal hygiene and grooming.

現在のところ数量化の兆しは無いが、多くの人々は、室内トイレ、洗濯ものに関する気高い社会規範、個人衛生、身繕いとともに改善された生活基準の影響とみている。[この辺はMcKeownのRole of medicineに詳しい]

Better oral hygiene can easily be seen as part of more meticulous personal hygiene and grooming rather than a conscious act to improve oral health.

口内衛生は、口内衛生の改善への意識的行為というより、行き届いた個人衛生と身繕いの一部であると思われる。[死語・廃語かもだけど、エチケット、ね]

As with the cyclical nature of other diseases over time, however, it is quite likely that there are factors operating that have not been identified (see discussion later in this chapter on the effect of the social environment).

長期的に見られるその他の疾病の循環性と同様に、齲蝕の減少は特定されていないファクターによるものなのかもしれない(社会環境の影響については本chapterの後半で論じる)。[2010.2.23]

The uneven distribution of caries

齲蝕の不公平な分布

For many years, the results of national surveys were presented only as mean DMF values, usually with only a standard deviation to indicate the distribution.

長年、全国調査の結果は、DMFスコアの平均値と標準偏差のみが公開されていた。[2010.2.24]

While means are valid and useful, they ‘compress’ extreme values, meaning those with no caries and those with a lot, into an average figure which sometimes can be misleading.

平均値は、妥当性があり便利であるが、極端な値を‘圧縮’する。つまり、齲蝕の無い人と齲蝕の多い人を、しばしば誤解をともなう、平均値に丸めてしまう。

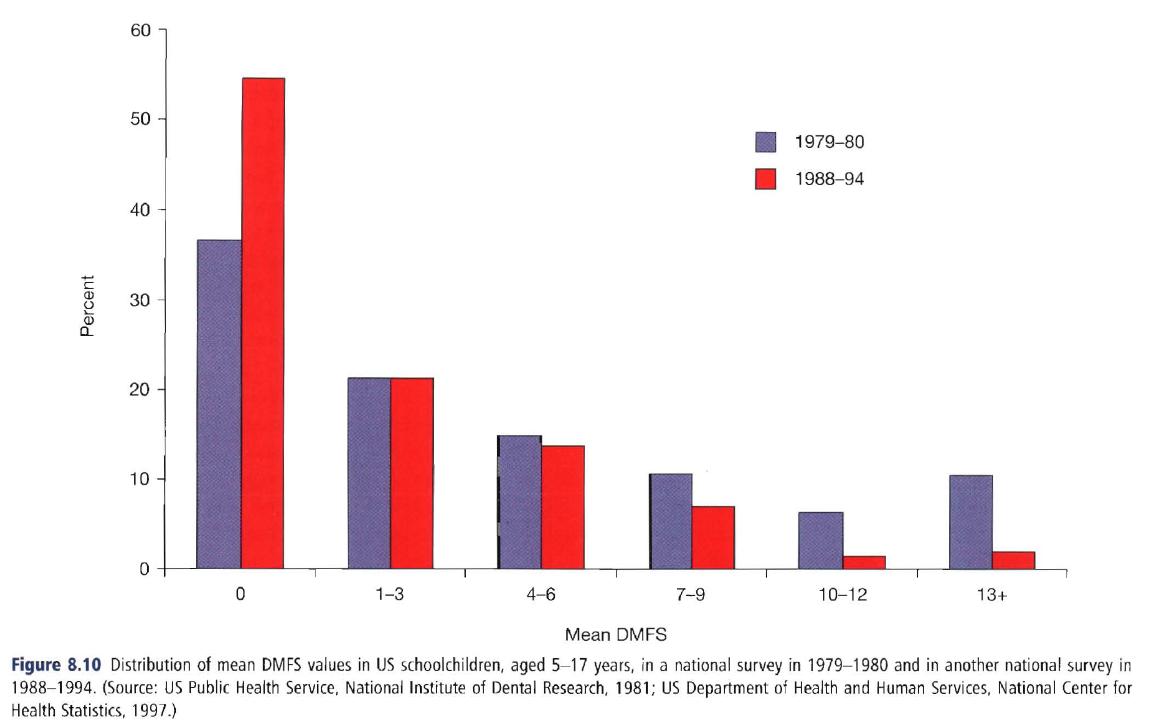

A break from this convention in the USA came with the results of a major preventive study in the mid-1980s, which drew attention to the fact that while average caries experience in children was lower than the researchers had originally expected, there was still a significant minority with severe caries (Graves et al., 1986).

USAでは、1980年代半ばに大きな予防研究があり、その前後の全国調査の結果を検討すると、小児の齲蝕経験の平均は、研究者が当初予想していたよりも低くなったが、重度の齲蝕を抱えたままの集団も、わずかながら存在している、という事実に注意が向けられるようになった (Graves et al., 1986)。

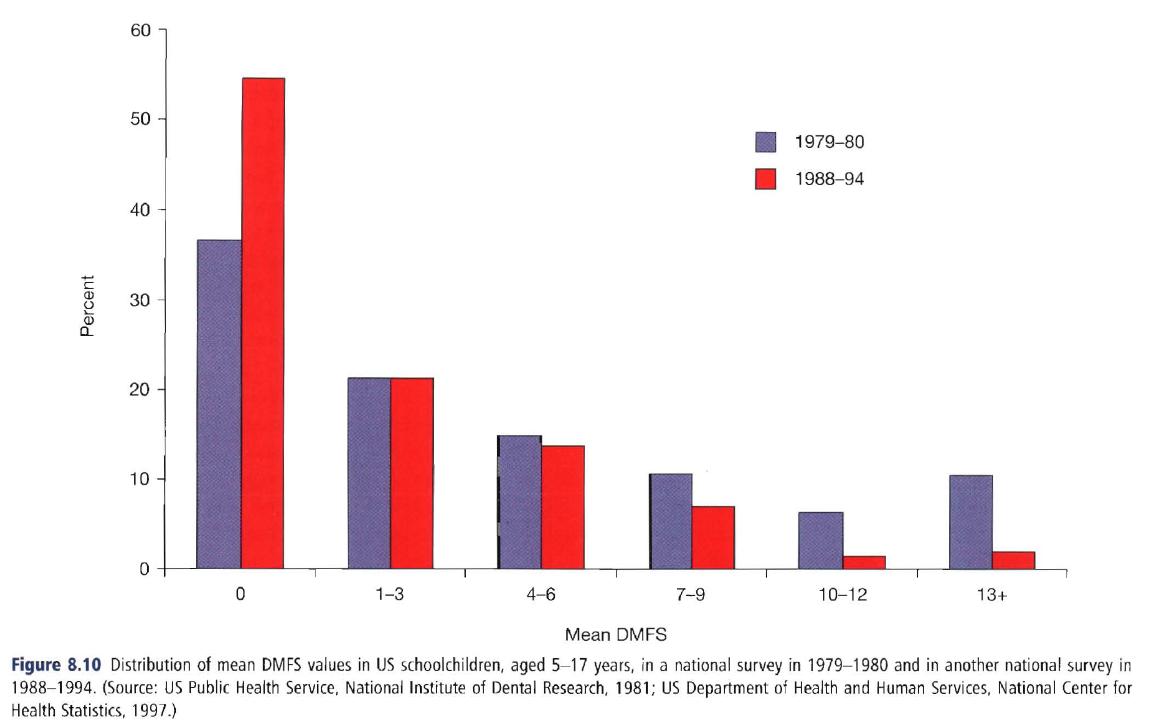

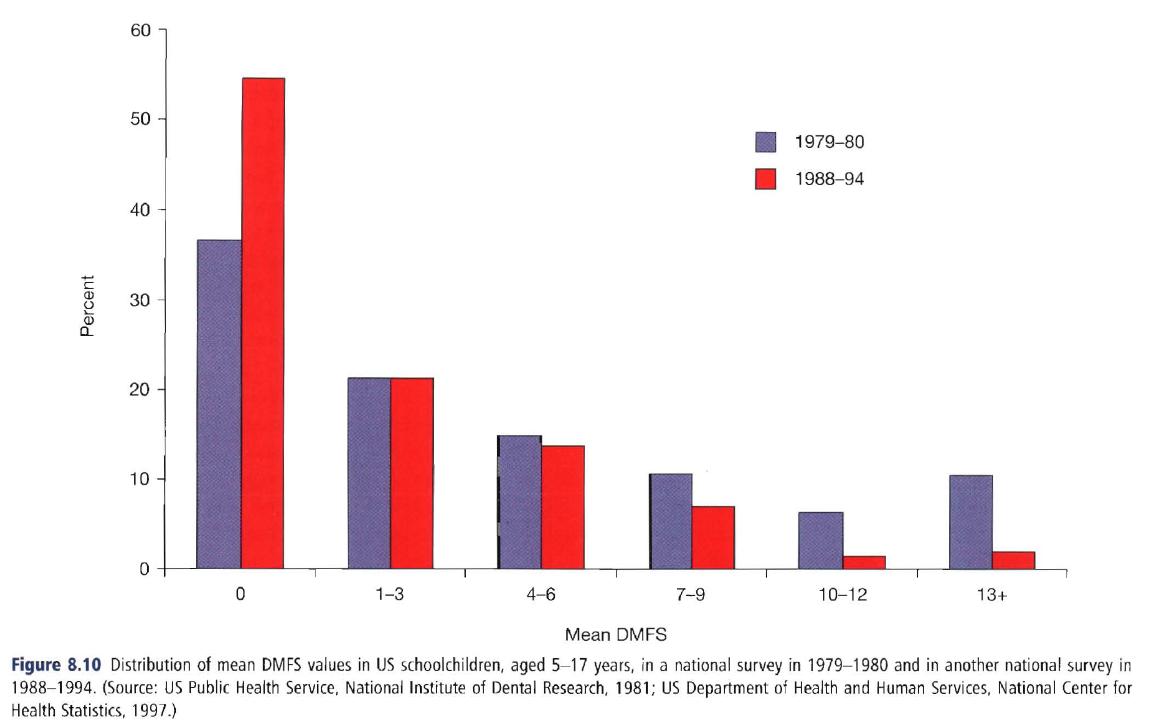

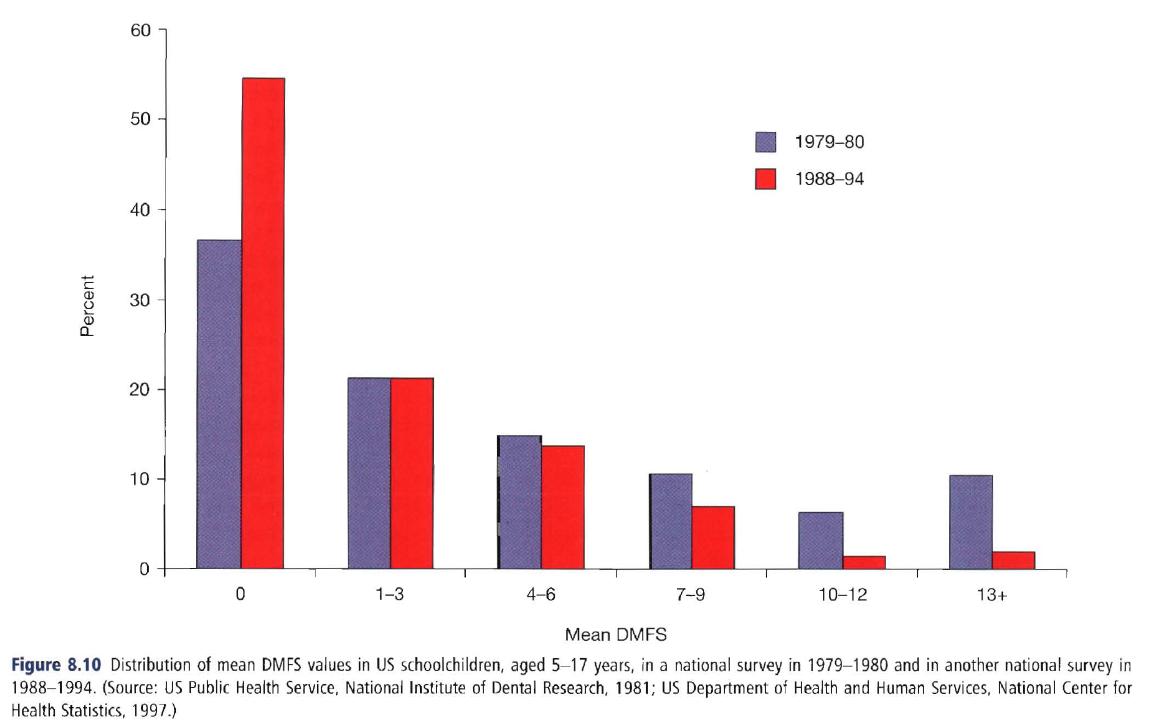

This type of distribution is illustrated in Fig. 8.10, which shows data from the US national surveys of schoolchildren in 1979-1980 and 1988-1994.

This type of distribution is illustrated in Fig. 8.10, which shows data from the US national surveys of schoolchildren in 1979-1980 and 1988-1994.

この分布の傾向をFig. 8.10に示した。1979-1980年と1988-1994年のUS学童全国調査の資料である。

Rather than mean DMF scores, this graph illustrates the distributional changes and shows a classic skewed distribution.

このグラフは、DMFスコアの平均値ではなく、分布の変化と古典的な傾斜分布を示している。

It is evident that in the more recent survey the proportion of children with low DMF scores had increased, while the proportion with high scores (i.e. severe caries) had decreased.

最近の調査では、DMFスコアの低い小児の割合が増えており、スコアの高い(重症な)小児の割合は減少している。

Even so, the shape of the distribution remained much the same: highly skewed toward zero or few DMFS teeth, but with a persistent ‘tail’, meaning children at the severe end of the scale.

そうであっても、分布の形はおおむね変わりない。DMFS歯スコア0近辺に大きな山があり、また重症を意味する分布の端に‘裾野’が伸びている。[中央値ないし最頻値が左に移動している、ってことね]

It is these children in the tails who are considered to be at high risk, and who thus absorb a lot of attention from public health services.

ハイリスクにあると考えられる小児は、この裾野の部分に存在しており、公衆衛生上の注意を引いている。

It is generally accepted today that in any population some 60-70% of all carious lesions are found in 15-25% of the children.

今日では一般に、どのような集団でも、小児の15-25%に全ての齲蝕の60-70%ほどが集中している。

Whether these children should be targeted for special preventive treatment or not remains a subject for active debate (see Chapters 28 and 29).

これらの小児を、特別な予防処置の対象とすべきかど齲窩は、活発な議論を呼んでいる(Chapter 28と29をみよ)。

Age and gender

年齢と性別

Mean DMF scores increase with age.

DMFスコアの平均値は、加齢とともに増加する。

Caries used to be considered just a childhood disease, a perception from those days of high caries severity when most susceptible surfaces were usually affected by adolescence.

青年期までに、最も感受性のある歯面が侵されていた頃、齲蝕は、幼児期の疾病であり、この時期から齲蝕は重症化すると認識されていた。

With younger people now reaching adulthood with many surfaces free of caries, the carious attack is spread out more throughout life.

現在、より若い人々は、多くの歯面に齲蝕のないまま成人しており、齲蝕の攻撃は、より人生を通じて広がっている。

Adults of all ages can, and do, develop new coronal lesions (Hand et al., 1988; Drake et al., 1994; Luan et al., 2000), and caries has to be viewed as a lifetime disease.

成人以降も、新たなる歯冠齲蝕は生涯にわたり進行しており (Hand et al., 1988; Drake et al., 1994; Luan et al., 2000)、齲蝕は一生涯の疾病であると見るべきである。

Even the skewed disease distribution seen in youth can be seen among the elderly (McGuire et al., 1993).

青年にみられる疾病の傾斜分布は、高齢者にもみられる (McGuire et al., 1993)。

In populations where caries experience is severe the disease starts early in life and is common in the young.

齲蝕経験が重い集団では、疾病は人生の早期から始まり、青年で蔓延する。

A more even occurrence of new lesions throughout life is characteristic of a lower community attack rate.

齲蝕水準の低い地域ほど、新たなる齲蝕は、[幼児期に集中するのではなく]人生を通じて均等に発生している。[2010.2.25]

Regarding gender, women usually have higher DMF scores than do men of the same age, although this finding is not universal.

性別の点で、女性は一般に同世代の男性よりDMFスコアが高いが、これは普遍的に見いだされることではない。[以下、Root cariesの後半より移動]

When observed in children, the difference has been attributed to the earlier eruption of teeth in girls, but this explanation is hard to support when the differences are seen in older age groups.

小児の男女の違いは、少女の歯の萌出の早いことに因っているが、その後の世代に表れている違いを見ると、この説明を支援することは難しい。

In those instances a treatment factor is more likely because in national survey data men usually have more untreated decayed surfaces than women, while women have more restored teeth.

後の世代を見てみると、全国調査では、一般に男性は女性より未治療の歯面が多く、女性は修復歯の数が多いため、治療ファクターがあるのかもしれない。

Women visit the dentist more frequently, so this observation is perhaps to be expected.

女性は男性よりも、頻繁に歯科を受診するので、これは、予想されることである。

In a national survey in the USA, girls aged 12-17 years had the same mean number of decayed and missing surfaces as their male counterparts, but 25% more filled surfaces (Kaste et al., 1996).

USAの全国調査によると、12-17歳の少女は、齲蝕歯面と喪失歯の平均値では少年と変わらないものの、修復歯面は25%上回っている (Kaste et al., 1996)。

One cannot conclude from these figures that women are more susceptible to caries than are men; a combination of earlier tooth eruption plus a treatment factor is a more likely explanation for the observed differences.

これらの数字から、女性は男性より齲蝕になりやすいと結論できる人は、いない。歯の萌出時期に治療ファクターを上乗せすれば、男女の違いを説明できそうだ。

P135

Root caries

歯根齲蝕

One important offshoot of the age-caries relationship is root caries, defined as caries that begins on cemental root surfaces exposed to the oral environment, and hence when bacterial plaque can accumulate around these exposed roots.

年齢齲蝕関係で忘れてはいけないのは、歯根齲蝕である。これは、口内環境に露出した歯根セメント質に生じる齲蝕で、それゆえ、露出した歯根周囲に細菌プラークが堆積すると生じる。

As mentioned above, root caries has been with humankind since our earliest days.

上記のとおり、歯根齲蝕は有史以来、人類に生じている。

Even so, awareness of root caries in the high-income countries only grew around the early 1980s with the realization that older adults were keeping more teeth than they used to.

とはいえ、高所得国家における歯根齲蝕が興隆を始めたのは、高齢者の残存歯がかつてより増えてきた、1980年代である。

Root caries is highly prevalent among older people in high-income countries (Salonen et al., 1989; Beck, 1993; Lo & Schwarz, 1994; Hawkins et al., 1998; Gilbert et al., 2001; Chalmers et al., 2002; Morse et al., 2002), although it too has declined in recent years, just as coronal caries has.

歯根齲蝕は、高所得国家の高齢者に蔓延している (Salonen et al., 1989; Beck, 1993; Lo & Schwarz, 1994; Hawkins et al., 1998; Gilbert et al., 2001; Chalmers et al., 2002; Morse et al., 2002) が、近年は歯冠齲蝕と歩みを合わせるように、減少してきている。

Figure 8.11 shows the decline in root lesions in the USA, despite greater tooth retention, between the two most recent national surveillance surveys.

Figure 8.11 shows the decline in root lesions in the USA, despite greater tooth retention, between the two most recent national surveillance surveys.

USAでは、直近2回の全国調査の間に、より多くの歯が残るようになってきているにもかかわらず、歯根病巣は減少してきている様子が、Figure 8.11に示されている。

Root caries, by definition, is strongly associated with the loss of periodontal attachment (Locker & Leake, 1993; Slade et al., 1993; Whelton et al., 1993; Lawrence et al., 1995; Ringelberg et al., 1996).

歯根齲蝕は、本質的に、歯周アタッチメントの喪失と、強固な関係がある (Locker & Leake, 1993; Slade et al., 1993; Whelton et al., 1993; Lawrence et al., 1995; Ringelberg et al., 1996)。

Other correlates associated with root caries are primarily socioeconomic: years of education, number of remaining teeth, use of dental services, oral hygiene levels and preventive behavior (Vehkalahti &Paunio, 1988; DePaola et al., 1989; Beck, 1993;).

そのほかの歯根齲蝕と関係のあるものには、学歴[いわゆるempowerment]、残存歯数、歯科医療の利用、口内衛生水準、予防行動がある (Vehkalahti &Paunio, 1988; DePaola et al., 1989; Beck, 1993;)。

Another important risk factor is the use of multiple medications among the elderly (Kitamura et al., 1986), a common practice in institutions, and one that can promote xerostomia.

そのほかの重要なリスクファクターは、高齢者の施設での慣行であり、また口内乾燥症を促進する多剤服用である (Kitamura et al., 1986)。

Xerostomia has long been known as a major risk factor for caries among people of any age, and is particularly prevalent among those who have received radiation treatment for cancer.

口内乾燥症は、あらゆる世代にとって齲蝕の大きなリスクファクターであるとして知られているところであり、がんの放射線治療を受けた人には、特に蔓延している。

Other risk factors identified in a representative British sample of people aged 65 or more were poor oral hygiene, wearing partial dentures, sucking candies in a dry mouth and living in an institution (Steele etal., 2001).

Britishの65歳以上の人々の代表標本からわかったそのほかのリスクファクターは、不良な口内衛生、傷んだ部分床義歯、口内乾燥によるキャンディーの吸啜、施設での生活であった (Steele etal., 2001)。

Root caries is less prevalent in high-fluoride areas than in low fluoride communities (Burt et al., 1986; Stamm et al., 1990), smokers exhibit more root caries than non-smokers, and prevalence tends to be inversely related to the number of teeth remaining (Beck, 1993; Locker & Leake, 1993).

歯根齲蝕は、低フッ化物地域より高フッ化物地域で、鳴りを沈め (Burt et al., 1986; Stamm et al., 1990)、非喫煙者より喫煙に多く、残存歯数に反比例して多くなる傾向がある (Beck, 1993; Locker & Leake, 1993)。[2010.3.2]

Root caries seems to be a particular problem among older people of lower socioeconomic status, those who have lost some teeth, who do not maintain good oral hygiene and do not visit the dentist regularly.

歯根齲蝕は、社会経済的地位の低い高齢者、何本か歯の無い人、良好な口内衛生を維持しない人、定期的にしか受診をしない人には、とりわけ課題となる。

Because of our aging populations and increasing retention of teeth, it could be that the dimensions of the root caries problem will continue growing in the years ahead.

加齢と残存歯数の向上のため、歯根齲蝕は、あと何年かは繁栄し続けるだろう。

However, the decline shown in Fig. 8.11 adds strength to the argument that root caries, while not exactly going away, will continue to diminish in the population.

しかしFig. 8.11に示した減少は、歯根齲蝕は、絶滅とはいかなくとも衰退し続けるという反論を支持する。[以下、Age and genderに移動]

P136

Race and ethnicity

人種と少数民族

Global variations in caries experience result from environmental rather than from inherent racial attributes.

齲蝕経験の世界的なばらつきは、人種によるものではなく、環境によるものである。

To illustrate that point, there is evidence that some racial groups, once thought to be resistant to caries, quickly developed the disease when they migrated to areas with different cultural and dietary patterns (Beal, 1973; Russell, 1966).

このことを示すため、さまざまな文化的食事傾向が混在する地域への移住により、当時齲蝕に耐性があると考えられていた人種が、さくっと齲蝕にかかってしまう、ということが検証された (Beal, 1973; Russell, 1966)。

In the United States, to choose one example of a multiracial and multiethnic society, most surveys before the 1970s found that whites had higher DMF scores than African-Americans, although the latter usually had more decayed teeth.

USでは、多民族社会の例を選ぶために、1970年代のほとんどの調査は、白人はアフリカ系アメリカ人よりもDMFスコアが大きいことを、明らかにしていたが、アフリカ系アメリカ人は、通常齲歯をより多く有していた。

One of the early national surveys in 1960-1962 showed that whites had higher DMF scores than did African-American adults of the same age group, a difference that remained even when the groups were standardized for income and education (US Public Health Service, NCHS, 1967).

1960-1962年の全国調査の1つは、同世代の成人を比較すると、白人はアフリカ系アメリカ人よりDMFスコアが大きいことを示しており、これは、収入と教育で標準化しても、変わりがなかった (US Public Health Service, NCHS, 1967)。

This difference was still evident in a national survey from the1970s (US Public Health Service, NCHS, 1981).

この差は、1970年代の全国調査でも確認された (US Public Health Service, NCHS, 1981)。

By the time of the 1988-1994 national survey, however, there was little difference in total DMF scores between whites and African-Americans, although whites still had a higher filled component and lower scores for decayed and missing surfaces.

しかし、1988-1994年の全国調査までに、白人とアフリカ系アメリカ人のDMFスコアの違いはほとんどなくなり、また白人のF値が高くなり、DとMのスコアは低くなった。

DMF values for Mexican-Americans were in between.

メキシコ系アメリカ人のDMFスコアは、その中間である。

This turn around probably reflects improving access to care for African-Americans, although it still reflects socio-economic and cultural contrasts between the groups.

この変節は、おそらく、アフリカ系アメリカ人の医療へのアクセスの改善を反映しているが、しかし、まだ集団間の社会経済的文化的なコントラストを反映している。

Even though overall caries experience in the permanent dentition continues to decline in the USA, disparities between racial and ethnic groups in the prevalence and severity of dental caries still remain in the twenty-first century (Beltnln-Aguilar et al., 2005).

USAでは、永久歯の齲蝕経験は減少し続けているが、齲蝕の広がりと重症度の人種間格差と少数民族間格差は、21世紀においても残っている (Beltnln-Aguilar et al., 2005)。

However, the overall pattern is that there is no evidence to support inherent differences in caries susceptibility between racial and ethnic groups.

しかし、人種と少数民族により、齲蝕感受性に違いがあるという検証はない。

Far more important are socioeconomic differences and contrasting social environments, meaning differences in education, available income and access to health care.

より重要なのは、社会経済的な違いと対照的な社会環境、つまり教育の違い、所得の違い、医療へのアクセスの違いにある。[へ?医療へのアクセスの違いが、齲蝕感受性に影響するって?]

More difficult to measure are long-held cultural beliefs that affect values and behavior related to dental health.

歯科保健に対する価値と行動に影響をもたらす、長年の文化的考え方を評価することは、難しい。

However, no one doubts that these factors are present and influencing caries incidence.

しかし、これらのファクターが存在し、また齲蝕の発生に影響していることを疑うような[鈍い]人は、いないだろう。

Familial and genetic patterns

家族傾向と遺伝傾向

Familial tendencies (‘bad teeth run in families’) are seen by many dentists and have been recorded (Klein & Palmer, 1938; Klein &Shimizu, 1945; Ringelberg et al., 1974).

家族傾向(‘悪い歯は家族を駆け巡る’)は、多くの歯科医師が遭遇するところであり、記録にも事欠かない (Klein & Palmer, 1938; Klein &Shimizu, 1945; Ringelberg et al., 1974)。

However, these studies have not identified whether such tendencies have a true genetic basis, or whether they stem from bacterial transmission or continuing familial dietary or behavioral traits.

しかし、これらの研究は、この傾向が遺伝に基づくのかどうか、あるいは細菌感染によるものなのか、はたまた家族の食性や行動習慣によるものなのかを特定していない

Husband-wife similarities clearly have no genetic origin, and intrafamlial transmission of cariogenic flora, especially from mother to infant, is considered by some to be a primary way for cariogenic bacteria to become established in children (Kohler et al., 1983; Caufield et al., 2000).

夫婦が似ていることは、明らかに遺伝的な原因ではなく、齲蝕原性細菌叢の家族内感染、とりわけ母子感染は齲蝕原性細菌が小児に伝播する第一の原因であると考えられている (Kohler et al., 1983; Caufield et al., 2000)。

The lack of a demonstrable genetic influence by race, discussed above, weakens the case for genetic inheritance of susceptibility or resistance to caries, although it is interesting that Klein, years ago, concluded that the similarities within families involved ‘strong familial vectors which very likely have a genetic basis, perhaps sex-linked’ (Klein, 1946).

上に論じたように、人種による遺伝的影響は明らかではないため、齲蝕への感受性や耐性の遺伝的継承の言い分は弱いのだが、Kleinが、家族間の類似性には、‘遺伝的、おそらく伴性の、強力な家族的媒介’が関与している、と結論したことは、興味深い (Klein, 1946)。

With the explosion of research discoveries of genetic influences in many diseases, dental caries is being looked at in a different light.

多くの疾病で遺伝の影響の発見が相次いでおり、齲蝕は、違った角度から見られている。

It is plausible that host attributes that could affect an individual’s caries experience, such as salivary flow and composition, tooth morphology and arch width, are genetically determined, and the genetics of the cariogenic bacteria themselves may have an effect.

唾液流量と構成、歯の形態、歯列弓の幅といった、個人の齲蝕経験に影響を与える宿主属性は、遺伝的に決定されており、齲蝕原性細菌の遺伝は、その影響を受ける、という言説は、はもっともらしい。

However, the ready preventability of caries, indicated by the caries decline, strongly counters (if not refutes) the idea of any genetic component worth mentioning.

しかし、齲蝕が予防できることは、齲蝕の減少により示唆されているが、(もし論破されなければ)遺伝的要素に言及する価値があるという概念に対する強力な反論となる。

At present, no genetic role in caries experience has been demonstrated.

現在のところ、齲蝕経験における遺伝の役割は明らかではない。

P137

Socioeconomic status

社会経済的地位

Socioeconomic status (SES), or social class, is intended to be a broad summary of an individual’s attitudes, values and behavior as determined by such factors as education, income, occupation or place of residence.

社会経済的地位 (SES)、あるいは社会階層は、教育、所得、職業、あるいは居住地区といったファクターにより決定される個人の姿勢、価値観、行動を要約することを目的としている。

[2010.3.2]

Attitudes toward health are often part of the set of values that follow from an individual’s social standing in the community, and can help to explain some of the observed variance in health measures.

健康に対する態度は、しばしば、地域における個人の社会的立場から生じる価値観群の一部であり、また健康評価において観察されるばらつきの一部を説明するのに役立つ。

Obtaining a valid measure of SES, however, is always a problem because of the construct’s complexity.

しかし、SESの妥当な尺度を得るには、つねに、 構成の複雑さゆえの課題をはらむ。

The most commonly used measures are income and years of formal education, despite acknowledged shortcomings with the latter measure (Hadden, 1996).

最も普及している尺度は、所得と、欠点があるにもかからわず、とされる教育年数[学歴]である (Hadden, 1996)。

SES is used in research as an attribute specific to the individual, rather than to the community.

研究では、SESは、地域ではなく個人の属性として、利用される。

It is usually inversely related to the occurrence of many diseases, and to characteristics thought to affect health (Marmot & Wilkinson, 1999).

SESは、一般に、多くの疾病の発生に、また健康にに影響を与えると考えられる特性に反比例している (Marmot & Wilkinson, 1999)。

The reasons for disparities in health status between various SES strata can often seem obvious, but that is not always the case (Link & Phelan, 1996).

さまざまなSES階層間の健康状況の格差の理由は、明らかであるが、つねに真実というわけではない (Link & Phelan, 1996)。[2010.3.3]

For example, higher infant mortality in lower SES strata can be partly explained by the facts that higher SES women have easier access to prenatal care, can better afford such care, and have more time to obtain it, a deeper educational base to permit better understanding of the condition and probably less fatalistic attitudes, and perhaps some other factors.

例えば、SES階層が低いほど乳児死亡率は高いことは、SESの高い女性ほどは、妊婦管理へのアクセスがよく、管理を受ける余裕があり、妊婦管理に多くの時間を割きやすいという事実、そして、より優れた体調の理解をもたらす深い教育的素養と、おそらくは希薄な運命論的態度、その他もろもろのファクターにより、部分的に説明されうる。

However, even after all these likely variables have been factored into explaining the differences, there is still a considerable gap which defies explanation (Fuchs, 1974).

しかし、これらのありえそうな変量の全てを、格差の説明にあてても、なお説明できない大きな格差が存在している (Fuchs, 1974)。

Measurements used in science cannot always pick up all the subtleties embedded in SES.

通常、科学で利用される尺度は、SESに滲みこんでいるニュアンスを汲み取ることはできない。

These subtleties have also been seen in dental health.

これらのニュアンスは、歯科保健についても、同様である。

In one Finnish study, for instance, differences in caries experience between children in the higher and lower social classes still remained after accounting for the reported frequency of tooth brushing, consumption of sugars and ingestion of fluoride tablets (Milen, 1987).

たとえば、Finlandの研究では、高い社会階層と低い社会階層の小児の齲蝕経験の違いは、報告されているブラッシング、砂糖の摂取、フッ化物タブレットの摂取の頻度を考慮しても、なお、残っている (Milen, 1987)。[2010.3.4]

These are all individual behaviors that would be more common in higher SES strata.

これらは、すべて高いSES階層には一般的な個人行動である。

Another instance comes from Sweden, where even with the extensive Swedish welfare system a social gradient in oral health is still evident (Flinck et al., 1999; Kallestal &Wall, 2002).

Swedenの例では、手厚いSwedishの福祉制度のもとでさえ、口内保健の社会的勾配は残っているという検証がある (Flinck et al., 1999; Kallestal &Wall, 2002)。[2010.3.7]

As part of his landmark research in caries epidemiology during the 1930s and 1940s, Klein observed that overall DMF values did not vary much between SES groups, but aspects of treatment certainly did (Klein & Palmer, 1940).

Kleinは、1930年代と1940年代の齲蝕疫学の画期的な研究の一部として、DMF値そのものはSES集団間で大きくは変化しないが、治療の面では変化するということを、示した (Klein & Palmer, 1940)。

Lower SES groups had higher values for D and M, lower for F.

低いSES集団は、D値とM値が高く、F値は低い。

In the first national survey of US children in 1963-1965, white children in the higher SES strata actually had higher DMF scores than did white children in the lower strata, but African-American children showed the opposite profile (US Public Health Service, NCHS, 1971).

1963-1965年の第1回US小児全国調査では、社会階層の高い白人の小児は、社会階層の低い白人の小児よりも DMFスコアが高かったが、アフリカ系アメリカ人の小児は反対の特徴を示した。

In the white children, the F component ballooned so much with increasing SES that it lifted the whole DMF index.

白人の小児では、SESが上がるにつれてF要素がふくれあがり、F要素はDMF指数全体を引き上げる。

By contrast, the F component in the African-American children did not change with SES, with the net result that their DMF scores diminished with increasing SES.

対照的に、アメリカ系アフリカ人の小児のF要素は、SESにより変化せず、その結果、DMFスコアはSESが上がるにつれて小さくなる。

As mentioned earlier, these results from 1963-1965 showed that a ‘treatment effect’ was artificially inflating the DMF data in the white children.

先に指摘したように、1963-1965年の結果は、‘治療効果’が白人小児のDMFを人工的に膨らませているということを示している。

In today’s lower overall caries experience, however, the position has been reversed.

今日、齲蝕経験全体は小さくなってきているが、この状況に変わりはない。

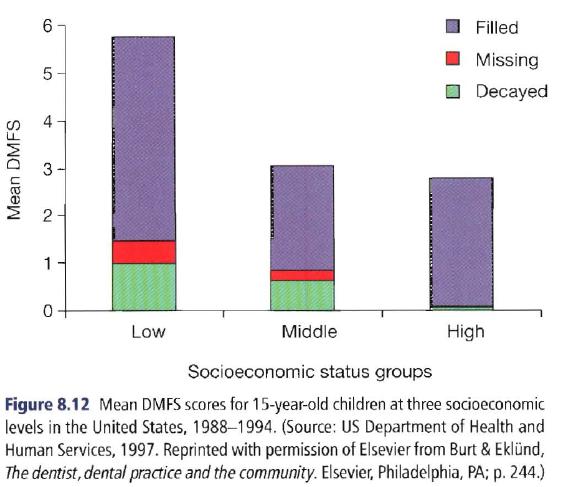

During the period when the caries decline was first recognized, it was soon found that the higher SES groups enjoyed the sharpest decline in caries experience (Graves et al., 1986), so that the DMF values of children in higher SES strata are now generally well below those of children in lower SES strata.

当初、齲蝕の減少が認識された時代に、SESの高い集団は、齲蝕経験の減少が急激であったため (Graves et al., 1986)、現在は通常、SESの高い小児のDMF値は、SESの低い小児のDMF値よりも小さい。

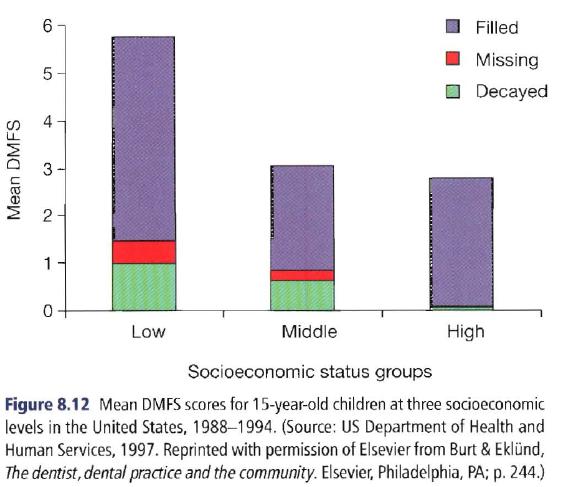

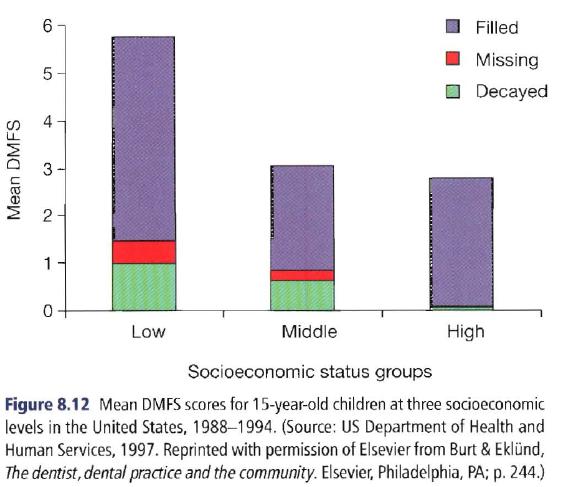

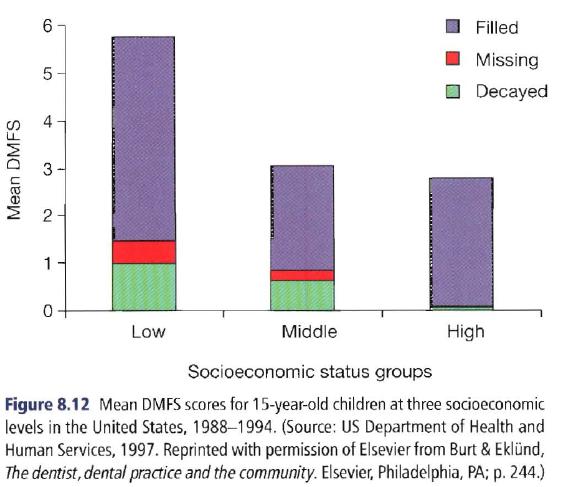

This is illustrated in Fig. 8.12, which shows the components of the DMFS index for 15-year-old children in low, medium and high SES groups from a national survey in the USA during 1988-1994.

This is illustrated in Fig. 8.12, which shows the components of the DMFS index for 15-year-old children in low, medium and high SES groups from a national survey in the USA during 1988-1994.

Fig 8.12は、1988-1994年のUSAの全国調査から、SESの低・中・高で分けた15歳児のDMFS指数の各要素を示している。

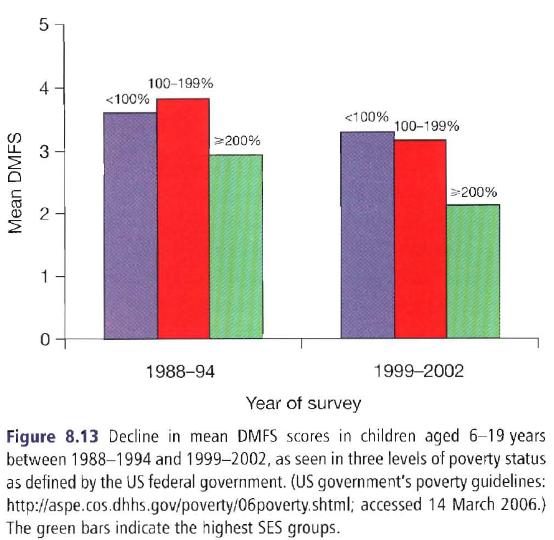

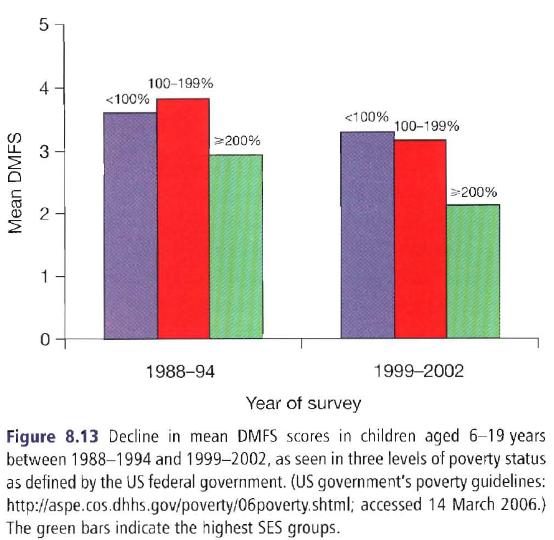

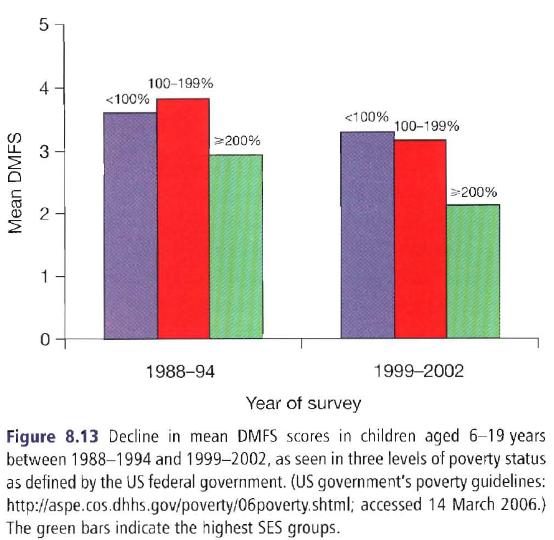

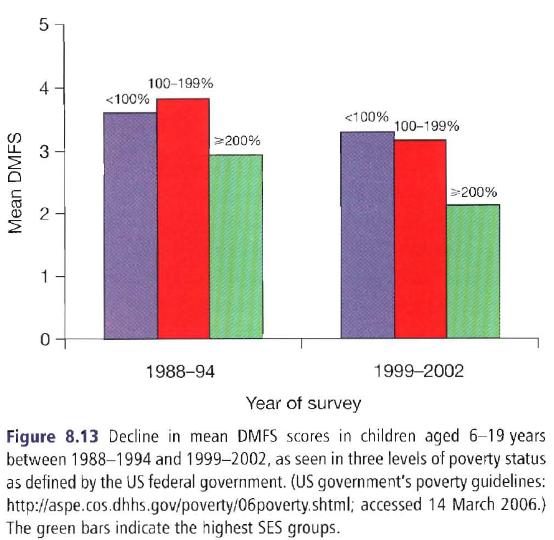

Figure 8.13 illustrates two features of the caries decline.

Figure 8.13 illustrates two features of the caries decline.

Figure 8.13は、齲蝕減少の2つの特徴を示している。[2010.3.8]

The first, the secular decline in caries, has already been illustrated (Figs 8.6-8.10) and is seen again with the reductions over time in each poverty-status group in Fig. 8.13, showing that, even over this fairly short period of 8-11 years, caries levels across all age and socioeconomic groups have continued to decline.

第1に、齲蝕の減少は、すでに示した通り (Figs 8.6-8.10) であるが、Fig 8.13に示された貧困な状況の集団のそれぞれにおいても、長期にわたる減少がみられ、8-11年というかなり短い期間に、あらゆる世代、社会経済的集団において齲蝕水準は減少し続けていることを示している。

The second aspect illustrated here is how caries levels are related to SES.

第2に、ここに示されているのは、齲蝕水準がどの程度SESに関連しているのか、ということである。

The children are grouped by poverty status as defined by the US federal government (a socioeconomic measure used to determine eligibility for government programs), and it can be seen that children in the higher SES groups (i.e. those at ≥200% of the poverty level) have lower caries scores than do children below the poverty level or only just above it.

小児は、US連邦政府により定義されている貧困状況(政府計画の資格を決定するために利用される社会経済的評価)によって分類され、Fig 8.13はSESの高い集団(貧困水準の200%以上に位置する集団)の小児は齲蝕スコアが、貧困水準あるいは、それより上の小児より低いことを示している。

P138

As noted above, it is difficult for any one measure to capture all the nuances of SES.

上記の通り、どのような評価であれ、SESのあらゆるニュアンスを汲み取ることは、難しい。

British studies have explored the issue by introducing broader measures of SES determinants, such as private housing and car ownership, that go beyond just education and income (Palmer & Pitter, 1988; Carmichael et al., 1989; Gratrix & Holloway, 1994).

Britishの研究は、教育と所得のみならず、私邸、自家用車の所有といった、SESの決定要因の広範な評価を導入し、齲蝕との関係を探索した (Palmer & Pitter, 1988; Carmichael et al., 1989; Gratrix & Holloway, 1994)。

These measures were all related to caries levels in the population.

これらの評価は、すべて、集団の齲蝕水準に関係していた。[これ、単なる交絡のような]

A better sense of coherence among poor parents of adolescent children, i.e. people who have a more structured life than do others in the same social circumstances, is related to lower caries levels among their children (Freire et al., 2002).

青年期の人々においては、両親の首尾一貫感覚が優れている(例えば、同じ社会環境で、他の人よりも、構造化された生活を送る)ことと、齲蝕水準が低いことは、関連している (Freire et al., 2002)。[sense of coherenceは首尾一貫感覚。self-efficacy自己効力感に似た概念か?][poor parentsのpoorは誤植か?]

This is an intriguing area for further research.

これは、将来の研究において、興味をくすぐる分野である。

Caries levels are also related to the degree of neighborhood deprivation, where several area summary measures have been used (Jones et al., 1997a; Jones & Worthington, 1999; Grayet al., 2000).

齲蝕水準は、近隣地域の剥奪程度に関連しており、いくつかの地域の要約指標が使われている (Jones et al., 1997a; Jones & Worthington, 1999; Grayet al., 2000)。

These broad measures of area deprivation lead directly into the role of social determinants.

これらの貧困地域の広範な評価は、直接、社会的決定要因の役割に直結している。

Caries and the social environment

齲蝕と社会環境

A useful definition of public health is ‘ ... assuring conditions in which people can be healthy’ (JOM, 1988) (with emphasis on the word can).

公衆衛生の便利な定義は、‘人々が健康に生活できる状況の保証’である(できるという表現に注目せよ) (JOM, 1988)。[though the organized effort of societyが入っていないと、どうもしっくりしませんが]

That covers everything from maintaining the stratospheric ozone layer to picking up the garbage, to providing recreational facilities, decent housing or dental care where needed.

公衆衛生は、成層圏のオゾン層を維持することから、ごみ拾い、娯楽施設やちゃんとした住居、必要とされる場所での歯科医療の提供まで、あらゆる活動にまたがる。[to pickingとto providingの接続詞が無いような]

While it stresses the public responsibility for a healthy physical and social environment, it still leaves room for individuals to exercise personal choice in their health-related behavior and how they use health-care services.

公衆衛生は、健康的な物理的社会的環境に対する公的責任を強調するが、個人が、保健関連行動と医療をどのように利用するかという個人的選択を行使する余地を残している。[2010.3.10]

The term social determinants is related to this definition in that it refers to factors that affect health outcomes for everyone in the community, and whose presence or absence influences the environment ‘in which people can be healthy’.

社会的決定要因という言葉は、地域に住むすべての人のヘルスアウトカムに影響を与えるファクターに言及する、という点で、公衆衛生の定義に関連しており、社会的決定要因の有無は、‘人々が健康に過ごせる’環境に影響を及ぼす。[and whoseのandって必要無いような]

Social determinants can include such factors as the quality of housing, extent of community services, availability of transport, prospects for employment, crime levels, and access to parks, open space and suitable recreational facilities.

社会的決定要因は、住居の品質、地域サービスの広がり、移動手段の利用可能性、雇用の見通し、 危険水準、公園や広場、娯楽施設へのアクセスといったファクターからなる。

There are substantial and well-documented differences in health status between people who reside in upscale areas and those who reside in more deprived areas.

上流階層に属する人々とより低階層に属する人々の間の健康状況の違いは、膨大かつ詳細に記されている。

These contrasts have been documented in a number of countries and in a variety of cultures, although they have been best studied in the high-income countries (Kaplan, 1996).

これらの対比は、多くの国々、さまざまな文化で記されているが、最もよく研究されているのは、高所得国家である (Kaplan, 1996)。

The data show with remarkable consistency that people who live in the more affluent areas are invariably in better health than those from poorer areas, and this observation has endured well over time (Syme & Berkman, 1976; Kaplan et al., 1987; Marmot et al., 1987; Haan et al., 1989).

この資料は、注目すべき一貫性をもって、より裕福な地域に住む人々は、つねに、貧困地域に住む人々より健康であるということを、示しており、また、この観察は長年にわたり認められてきている (Syme & Berkman, 1976; Kaplan et al., 1987; Marmot et al., 1987; Haan et al., 1989)。

This finding is not dependent on how health status is measured, for it has been documented in terms of overall mortality, heart disease, diabetes or even subjective perceptions of ill-health (Pappas,1994; Blane, 1995; Kaplan et al., 1996; Link & Phelan, 1996; Goodman, 1999).

この発見は、全死亡率、心臓疾病、糖尿病あるいは健康障害の主観的知覚の点から記録されているため、どのように健康状況を評価したのか、には依存しない (Pappas,1994; Blane, 1995; Kaplan et al., 1996; Link & Phelan, 1996; Goodman, 1999)。

While there are numerous individual behavioral determinants involved in this profile (e.g. smoking, use of alcohol, quality of diet, regular exercise), there is also evidence that social determinants, i.e. those risk factors that apply to the whole community rather than to specific individuals, play a key role in determining health outcomes.

社会的決定要因は(喫煙、飲酒、食品の質、日常の運動といった)膨大な数の個人行動に関係しており、またヘルスアウトカムの決定に、重要な役割を演じている、という検証もある。そしてこれらは、特定の個人のみならず、地域全体に適応される。

When any of these basic community necessities are deficient or absent, the quality of life is diminished.

これらの地域の基本的要素のいずれかが、欠けたり不足したりすると、生活の質は低下する。

When they are mostly deficient, as is not uncommon in rundown parts of major cities, quality of life is diminished to the degree that a high level of emotional stress ensues from the demands of day-to-day coping with the cumulative burden of living in deprived circumstances.

これらがほとんど失われていた場合、これは大都市の荒れ果てた地区では珍しいことではないが、生活の質は低下し、貧困環境での生活による累積した重荷に対応する日々からくる高度な感情的ストレスが続く。

Poor social circumstances are linked to disease by way of material, psychosocial and behavioral pathways.